The Necessary Tools

by Janet Penn

The more culturally diverse we become, the more adept we need to be in relating to people who hold profoundly different beliefs. What questions help you truly understand someone, especially someone with whom you have a fundamental disagreement? How do you engage people from different backgrounds when addressing community problems?

People who learn these skills in their teens are able to decrease polarization at college, in the work place, and in interfaith communities where most of us live today. That was the goal we set for ourselves at Youth LEAD (Youth Leaders Engaging Across Differences), a project which began in Sharon, Massachusetts, in 2004. It provides interfaith leadership training for approximately 50 teenagers each year, young people who have gone on to responsibilities and projects receiving national attention and commendation. And now, collaborating with interfaith and community organizations, Youth LEAD is creating partner communities across Massachusetts and the country.

The learning sounds simple but is not easy to absorb. Acquiring reconciling habits requires time taken reflecting on your own values and beliefs. It calls for specific skill-sets along with the confidence to reach out and connect across the widest chasms of difference. And for teachers and facilitators, it requires a profound conviction that youth and young adults deserve a vital, collaborative role in addressing local and global challenges, right now.

Reflect

Youth LEAD (YL) participants each begin with the challenge of articulating what they believe to the whole group. Doing so provides a fresh clarity about their beliefs and opinions and creates confidence and a stronger sense of self, important steps in being able to communicate with people who disagree. A young person, clear and secure in his or her own faith, is not just “going along” with what “I’m supposed to believe” and is less likely to feel threatened by others or feel the need to convert them. Indeed, a democracy depends upon citizens being able to understand why they hold their beliefs and how to defend them, rather than attacking or blindly following the pack.

Connect

Active listening is the necessary foundation for sharing matters of the heart. Rather than trying to convince someone that he or she is wrong, YL encourages teens to ask clarifying questions: “I heard you say that this is important to you. Did I understand you correctly?” “What does that mean to you?” After watching a film about how different families coped with the effects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, teens facilitated a discussion. “I remember how varied the opinions were in our group,” said Ayesha. “Instead of sparking a debate, as I had typically seen happen in school and other places, this led to an interesting discussion about the opinions presented… It was a beautiful sight – dialogue in the midst of pessimism and war.”

Act

In the context of personal reflection and with the skills of engaging each other respectfully, high school students have what they need to plan and run programs that develop a healthy culture of pluralism. Instead of creating a curriculum for teens, teens are asked to identify barriers or problems among different religious and ethnic groups in their own communities and to propose ways to address them.

Five years ago a 16-year-old Youth LEADer decided to create an interfaith conference to expose more young people to the power of interfaith dialogue. After three years, a new cohort of youth decided to turn The Teenage Identity and Diversity Education Conference (TIDE) into a three-day teen-run program, now held each Memorial Day weekend at Northeastern University in Boston. “I was given the immense responsibility of leading a group of teenagers to productively plan a weekend-long conference,” says Aaron, a Jewish participant now attending Middlebury College. “During the actual conference, I gave a speech, led many workshops and dialogues, and made announcements to keep the conference running smoothly.”

Adults can provide young people with dialogue questions. But until we teach them to develop their own questions, they are ill-equipped to lead respectful conversations about polarizing topics that emerge spontaneously at school, a workplace, or anywhere else. Adults can plan a youth diversity conference, but until young people learn how to plan and run their own programs, they may not know how to transform problems into opportunities.

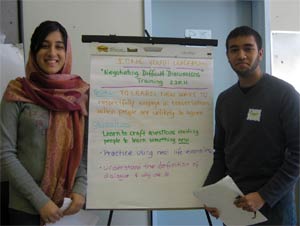

Leadership Training

Of course, this is not about “We’d like you to organize next year’s conference – so get back to us when you’ve decided what you want to do.” It is about leadership training. Youth LEADers complete six day-long training sessions that focus on skill-sets in three arenas – communication, facilitation, and organizing. Adult mentors working with teen participants take a day-long mentoring workshop.

- Communication – Basic Skills & Managing Difficult Conversations These two trainings focus on the skills and confidence needed to respectfully communicate one’s own identity and actively listen to the life experiences of others. Participants learn to craft questions that invite people to learn something new, rather than “the same old argument.”“My communication skills have helped me in every single aspect of college,” says Talia, “from compromising about music volume with my gospel belting roommate to interacting with professors. The acceptance for others I’ve learned has helped me make friends and connect with people who are not similar to me and to speak about my religion in a way people understand.”

- Introduction to Facilitation, Advanced Facilitation, & Dialogue Facilitation Tomorrow’s leaders will be called not only to engage in difficult conversations but to actively engage others. YL’s three facilitation workshops focus on skills needed to speak comfortably in front of a group, give and receive feedback in a self-affirming way, and lead group discussions. For topics usually too hot to handle, participants learn tools to facilitate a structured dialogue.“I'm probably the person who's most likely to mediate a discussionabout different views or ask deep questions about someone else's point of view,” shares Daisy, a Youth LEAD alum and Christian Scientist now at Bowdoin College.

- Organizing a Better World In mastering communication and facilitation skills, youth come to know what they believe. They have learned to ask engaging questions and understand people with different beliefs. They know how to facilitate difficult conversations. Now comes the time to act and fix what’s broken in their community. Project management training provides skills for creating and implementing programs that create a culture of pluralism. Participants learn to transform problem statements into a vision with goals and objectives. The training provides tools for creating and executing a plan and then de-briefing successes and failures.“The organizational and leadership skills that I gained in Youth LEAD allowed me to become a student leader right away at Tufts,” says Dan. “I was able to lead meetings with other students, craft an agenda, identify likely challenges, and demand responsibility and organization from others… The skills I gained at Youth LEAD prepared me to be a leader right away on campus.”

Mentors

Building the confidence to speak against intolerance and engage others requires feedback and guidance from adult mentors who’ve learned not to try to control the outcome. A teen’s vision and action steps may not look like yours or mine. Accepting that graciously can be the most difficult aspect of being a mentor. As we nurture and support, we must be willing to let go, even if it means the project doesn’t meet our goals, or ultimately, their expectations.

During a preliminary 2010 TIDE planning meeting, a faculty member from Northeastern University noted that the teen’s plan to engage in community service on Memorial Day was unrealistic since most non-profit organizations wouldn’t be open. I agreed and passed along the feedback to the teen committee coordinating the community service program. They decided to pursue their plan anyway. After weeks of phone calls, they discovered the faculty member was right – few sites were available and they changed their plan. I asked, “Are you sorry we didn’t insist that you change your plan?” The committee answered with a resounding No! “We learned a lot from making the calls and finding out for ourselves that our plan wouldn’t work.”

Outcomes of Skill-Based Interfaith Youth Programs

Based upon a three-year study of enrolled teens and interviews with alums, we’ve begun to see patterns that corroborate what individual teens have said anecdotally for years.

Youth who attend YL meetings have a more nuanced understanding of groups of people, clear about the wide variety of beliefs and practices within any group. Youth who go on to leadership roles, facilitating dialogues and chairing projects, note that their family and school groups are also positively impacted. “I was able to educate my extended family in India on different faiths,” says Divya, now a sophomore at Mt. Holyoke College, “dispelling many myths and untruths they may have heard elsewhere.”

Talia agrees. “If I saw a lack of tolerance of other religions being shown by members of my family or religious community, I would question or call them out because of Youth LEAD,” she says. “It made me look at the reasons why people believed what they do and motivated me to make those around me more accepting.”

Attitudes, habits, and behaviors are complex and form over many years. They do not change in two or three weeks, even with the most brilliant intervention or peace program. Youth LEADers long-term engagement is critical in changing not only their own habits and beliefs, but also challenging stereotypes held by their family and community. When Youth LEADers bring people together on a local level and reap positive, tangible results, it shows young people and their communities that it is possible to change things for the better.

“I believe that I became more optimistic regarding the potential of diverse members of a community to work together for the common good,” says Dan. “Even as I follow international conflicts and learn theories that suggest we are on a path to a cultural clash, I always remember that at least in my home community that was not the case.”

Youth LEAD has sourced leadership training programs for more than 4,000 teens since 2004. Founder and director Janet Penn has taught the model across America and in Jordan and India. YL has been recognized as an exemplary program by Harvard’s Pluralism Project and UNESCO. Youth LEAD’s website brings you up-to-date about the group’s current activities. Ed.