By Ruth Broyde Sharone

LANGAR, THE GOLDEN TEMPLE, EGALITARIANISM, AND THE SIRI GURU GRANTH SAHIB JI

I awoke at 3:00 am and sat bolt upright in my bed. Where was I? Then I remembered… in Amritsar, India, with a population of 2.5 million, and home to some two million Sikhs. I was about to visit the Golden Temple (or Harimandir Sahib), the Sikhs’ sacred shrine and spiritual lodestone.

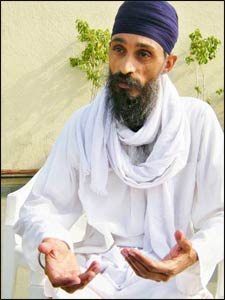

Nirinjan Singh Khalsa – Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

A treasured interfaith colleague, Nirinjan Singh Khalsa, knocked on my door at the Grace Hotel an hour later. “I’m ready,” I called out, opening the door to greet an American Sikh, executive director of the California Sikh Council. This was my first trip to India. Nirinjan, who converted to Sikhism more than 40 years ago, has traveled to Amritsar more than a dozen times. Now on his turf, I sensed how pleased he was to be my guide.

We walked in silence through the darkness. I noticed a flurry of activity in the streets, even at four in the morning, for the Golden Temple is openand welcoming to pilgrims and local people all day and night. Many visitors– wrapped up like mummies in colorful blankets – were sleeping on the marble stone floors of the Perkarma, the immediate area surrounding the Temple.

Soon they would be performing their morning ablutions, called “dipping,” in separate pools for men and women, or in the purified waters of the lake that borders the Temple on three sides.

The Golden Temple in Amritsar, on the right, with related buildings on the left, at night – Photo: Wikipedia

I caught my breath when I saw the golden structure floating on the water. In the dark the Golden Temple gleams like a brilliant jewel lighting up the black heavens and casting a thousand golden reflections on the lake below.

Nirinjan told me I was about to witness how the Siri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, the living scripture of the Sikhs and considered to be the last of their ten gurus, would be taken out of the Golden Temple and carried on a golden litter among the devotees. As the ceremony began, waves of chants rose and fell as thousands of Sikhs lavishly showered their holy book with fragrant flower petals. The sweet-smelling shower of pink, white, and yellow petals descended upon us. We stayed for a while, listening to the chants.

Nirinjan suddenly pressed his fingers to his lips and pointed behind me. I heard what sounded like a combination of a ram’s horn and drum rolls. Turning, I watched the Sikh holy book, having made its rounds, now being returned on its litter in the Golden Temple until dawn the next day.

The Long Road to Amritsar

I first learned about Sikhs in the seventies living in New York. An anthropologist studying Sikh culture introduced me to a group of Sikhs. It wasn’t until after 9/11, however, that I realized the vast majority of Americans knew little to nothing about the Sikhs who live among us. After the tragedy, we saw Sikhs being targeted and killed by misguided Americans who assumed every turbaned person is a potential Muslim terrorist. It happened again in 2013, in Wisconsin, where seven were killed.

My most personal experience with Sikh culture came during the 2004 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Barcelona, Spain. The Sikh community of Birmingham, England, served langar (free vegetarian meals) to 3,000-5,000 Parliament participants twice daily for an entire week, an unforgettable act of hospitality and a hallmark of Sikh culture.

Now, in Amritsar, I was prepared to go deeper and learn more.

Parvinder Singh – Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

After witnessing the dawn ritual, I met Nirinjan’s good friend, Parvinder Singh, a tall, gentle figure, dressed in white, with deep-set, dark eyes. We took the elevator to the rooftop of the Sapphire Tower, overlooking the brilliant sanctuary and its surrounding structures.

“The Golden Temple represents our soul,” Parvinder explained metaphorically. “It is surrounded on three sides by water just as our own bodies are made up primarily of water. The Temple reminds us of who we are and how we are connected to the One God – like the pathway over there that spans the water and connects to the Golden Temple,” he pointed out.

Parvinder had recently returned from Europe and Latin America, lecturing on Sikhism and demonstrating how the Sikh chants powerfully affect the body through the vibrations they create when uttered aloud.

An Interfaith Friendly Religion

An interfaith activist at heart, Parvinder spent many years studying Islam and Hinduism in addition to Sikhism. He said the actual foundation of the Golden Temple was designed by a Muslim architect and built with the help of Muslim and Hindu workers working together with Sikhs – music to my interfaith ear.

Guru Nanak (1469-1539), the first Sikh Guru and founder of the Sikh religion, was raised a Brahmin Hindu; but he was vehemently opposed to the caste system which dominated Indian and Punjabi society at the time, and discrimination of any kind. Nanak was critical of the way women were treated, believing that women, the creators of life, need to be honored and revered.

In particular, he was unwilling to accept the strict delineations among the four castes that had created a population of “untouchables.” In those times, untouchables were not even allowed to walk on the streets next to Brahmins, lest their shadows intersect, Parvinder said. When it happened, the Brahmins immediately cleaned the streets and went home to shower, considering themselves ‘contaminated’ through shadow contact! Guru Nanak found this intolerable. “He believed in equality for all, and believed that God was accessible to every man and woman at all times.”

Sikhs were forced to defend themselves against oppressive rulers time and again, especially in the 17th century. While never initiating a battle, Parvinder underscored, Guru Nanek and the successive Gurus enjoined Sikhs to be at the ready “to defend themselves, their families, and the defenseless.”

In 1699 major Sikh traditions were firmly established. These include donning a turban to identify themselves publicly as Sikhs; wearing a stainless silver bracelet, denoting devotion to Sikh principles; keeping their hair and beards (for the men) untrimmed but neat with a comb to symbolize cleanliness; wearing special undergarments for modesty and to be prepared for battle; and strapping on the dagger that today symbolizes the Sikhs’ historic and contemporary prowess in battle.

A most painful chapter in Sikh history grew out the struggle, largely in the 1970s and 80s, between India’s government and certain Sikh activists seeking to create a separate country called Khalistan. In 1984, without warning, Parvinder noted, Indian security forces stormed the Golden Temple with tanks and guns and murdered hundreds, perhaps thousands, of innocent Sikh men, women, and children. The actual number killed has never been established.

The government claimed at the time to be searching for political terrorists. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was subsequently assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards, in retaliation, followed by thousands more Sikhs being killed in other cities in India. That year was a very dark moment in Sikh history, Parvinder acknowledged sadly.

Professor Balwant Dillon – Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

At the Golden Temple, the 1984 bullet holes are still visible next to semi-precious stones embedded in the intricately carved marble wall tiles. The anger and resentment that massacre caused is still apparent when you speak to Sikhs today.

“We Sikhs will eventually forgive and move on,” Professor Balwant Dillon of the Guru Nanak University assured me when I paid him a visit the following day. Dr. Dillon, who has written ten books on Sikhism, was obviously taking ‘the long view.’ As a Jew with the memory of the Holocaust still a lingering source of pain for me, I felt a deep connection to the Sikh community when I heard details of the 1984 massacre.

I discovered other similarities between Sikhism and Judaism. One striking parallel is the Sikh’s deep reverence for their holy book, essentially a collection of devotional hymns, and their tradition of chanting aloud, just as Jewish communities chant aloud from our Torah, also deeply revered.

For another take on what it means to be a Sikh, watch this short video “Don’t Freak, I’m Sikh,”by Pardeep Bahra, a young Sikh in London.

Returning home to LA, I recalled the early morning visit to the Golden Temple. As we were leaving, people were still arriving in droves, their faces alight with anticipation. On our way out, Nirinjan bowed and touched the ground near one of the many shrines we passed. Straightening up, he pressed a generous portion of fragrant petals in my hand, the same petals tossed heavenwards earlier when his holy scripture passed by. “Here is something you can take home to remember this visit,” he said.

I still have those petals. Their lingering fragrance never fails to summon up a memory of a golden moment at the Golden Temple and my gratitude to the Sikh friends who taught me about their religion and revealed yet another facet of God’s infinite love. As Niranjan and Parvinder would say: “Waheguru: Great is the God who flows through all.”