Seek Peace and Pursue It

The Jewish Imperative for Peacemaking

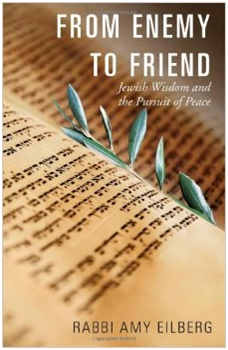

by Rabbi Amy Eilberg

This article is adapted from Rabbi Eilberg’s From Enemy to Friend: Jewish Wisdom and the Pursuit of Peace (Orbis, 2014).

* * *

The Rabbis of the Talmud observed that most legislation in the Torah is case law. If we find a lost object, we are to return it to its owner. If we own property, we must take precautions to ensure the safety of those who enter it. If we see our enemy’s animal struggling under its load, we are to help him. When Shabbat (Sabbath) or a holy day comes, we are to observe it.

Notably, two commandments are explicitly articulated not as responses to a particular situation, but as imperatives to be followed – indeed, pursued – at all times. We are not only to act in accordance with these imperatives passively when the occasion arises. We are to actively seek out opportunities to engage in them. The two cases are the pursuit of justice, of which it is said, “Justice, justice shall you pursue” (Deut. 16:20) and the pursuit of peace, of which it is said, “Seek peace and pursue it” (Ps. 34:15).

The rabbis assume that every apparently superfluous word in the sacred text is there for a reason. In this case, they implicitly ask why the verse employs two verbs (“seek” and “pursue”) when one would have sufficed. Their answer: “Seek it in your place and pursue it in another place” (Babylonian Talmud Perek Hashalom and Jerusalem Talmud Peah 1:1). The two verbs convey different elements of the command: seek peace when conflict comes to your doorstep, but do not stop there. You must energetically pursue opportunities to practice peace, near and far, for it is the work of God.

The Hafetz Hayim, pen name of Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (1838–1933), continues the tradition’s musing on the verse, teaching:

“Seek it (peace) for your loved one and pursue it with your enemy. Seek it in your place and pursue it in other places. Seek it with your body and pursue it with your material resources. Seek it for your own benefit and pursue it for the benefit of others. Seek it today and pursue it tomorrow.” With reference to “seek it tomorrow,” it teaches that one should not despair, thinking that one cannot make peace, but rather one should pursue peace today and also tomorrow and on the day afterwards, until one reaches it (Sh’mirat Halashon – Minding Speech, Gate of Remembering, chap. 17).

Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan, 91, on a visit to the Polish prime minister. – Photo: Wikipedia

Rabbi Kagan expands on the earlier interpretation, elaborating on the verse’s message to reach beyond one’s home and comfort zone in the pursuit of peace. What is called for, he insists, is not passive or occasional practice, but a constant, relentless seeking after opportunities to respond to the command.

We are not to wait for conflict to come to us before offering a peaceful presence; we must actively seek out ways to help. We are to practice peace with those nearest to us and with those we would prefer to avoid.

We are to make the pursuit of peace central to our relationships, both with those we love and with those we might consider to be enemies. We are exhorted to build peace both at home and when in foreign territory. We are to seek peace every day of our lives.

But then the Hafetz Hayim adds his own striking addition to rabbinic reflections on the pursuit of peace: “With reference to ‘seek it tomorrow,’ it teaches that one should not despair, thinking that one cannot make peace.” Clearly, historical circumstances impelled him to urge his followers not to lose hope about the prospect of peace.

Many years later, I identify with his impulse to counsel hopefulness and perseverance in the pursuit of peace, for I encounter so many people who are discouraged and disdainful about the prospect of conflict transformation in their lives and in the world. This sense of hopelessness, fear, and anger has been bred in us by many decades, or even centuries or millennia, of trying, without success, to live in peace with our neighbors.

Although we might think of the demon of despair as a uniquely contemporary obstacle to the practice of peacebuilding, the rabbi exhorts his people not to allow hopelessness, discouragement, or compassion fatigue to keep them from responding to the command to seek and pursue peace. Rather, he says, we must live out this sacred directive one day at a time, and then the next day, and then the next. He whispers words of encouragement: if we all begin to live this way, then yes, peace will come.

Header Photo: Wikimedia