The Jewish Jesus in the California Desert

A Report from The Tabernacle Experience

by Jonathan Homrighausen

I stood in front of the Ark of the Covenant, holding my incense while I gazed on the golden wings of the cherubim.

No, I am not starring in a remake of Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was inside The Tabernacle Experience, an interactive re-enactment of the Tabernacle which the Israelites built in the desert on their journey from Egypt to Canaan. The Tabernacle Experience, founded by evangelical Christian Jeanne Whittaker in response to a call from God to bring the Tabernacle to her own church for a women’s retreat, travels from church to church around the country. I recently had the privilege of lighting the menorah and offering a sacrifice on the horned altar of the Tabernacle set up on the lawn outside Calvary Community Church in Manteca, California.

As a graduate student in biblical studies, I was spiritually and intellectually captivated by the experience. As an advocate of interfaith dialogue, I was also struck by how the Tabernacle Experience encapsulated a central difficulty of Jewish-Christian dialogue: How do we articulate the Christian message, which defines itself as the fulfillment of Judaism, while simultaneously respecting and loving Judaism and Jews today as fellow people of God?

Some historical background: before Solomon’s Temple, there was the Tabernacle. As the newly freed men and women of Israel journeyed to Canaan, they continually erected, took down, and re-erected the Tabernacle as their mobile sacred space. The Tabernacle stored the tablets on which the commandments of God delivered at Sinai were written.

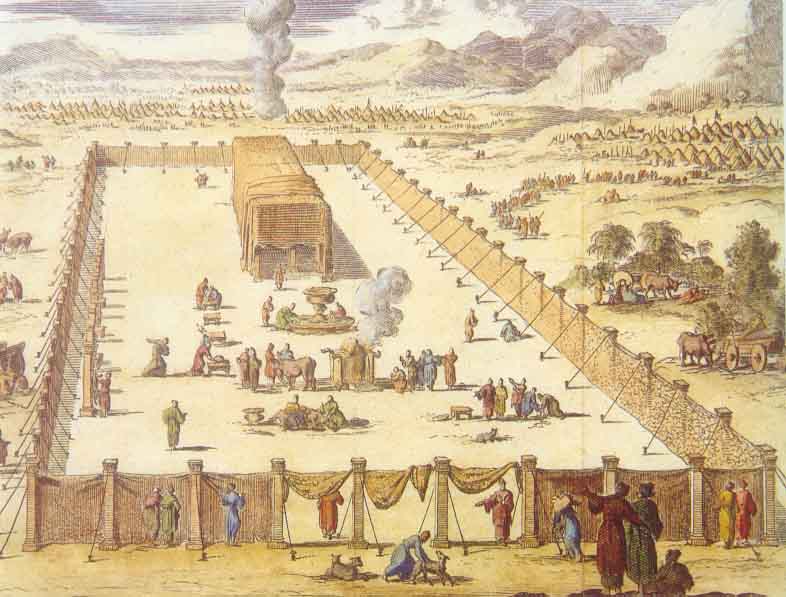

A painting of the Tabernacle designed from the instructions in Exodus 25-27 – Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As described in Exodus 25–27, the Tabernacle contained multiple levels of sacred space, from the courtyard to the holy place to the most holy place – the “Holy of Holies” in biblical idiom. Though the Tabernacle was taken down and the Ark later transferred to Solomon’s Temple, many of the Tabernacle’s rituals continued into the Temple as well. So this reconstructed Tabernacle also contained elements of the Jewish Temple that Jesus himself frequented.

Modern Christians generally don’t pay the complex ritual instructions of the Torah much mind. But any first-century Jew, including Jesus, Paul, and Matthew, would have been familiar with the Temple as a physical (until 70 CE), symbolic, and theological focus of Jewish faith and identity. Various writers of the New Testament connect Jesus with the temple, most famously in the theology of Jesus as High Priest. This is based on a passage in the New Testament’s book of Hebrews (4:14), where it says, “Since, then, we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast to our confession.” But for most of my life as a Christian, these metaphors have been lost on me.

Visiting the Tabernacle Experience changed that. As my wife and I moved around the courtyard, we donned the white linen temple garments, threw a wood shim on a horned altar to represent sacrificial atonement, purified our hands in the water of the laver, and gave a shekel as offering. Going inside the holy place, we symbolically ate bread dipped in wine (a Cheez-It in grape juice), lit a candle of the menorah, and watched as the smoke of the incense rose like a prayer. In the most holy place, we stood around the Ark of the Covenant and offered our prayer to God.

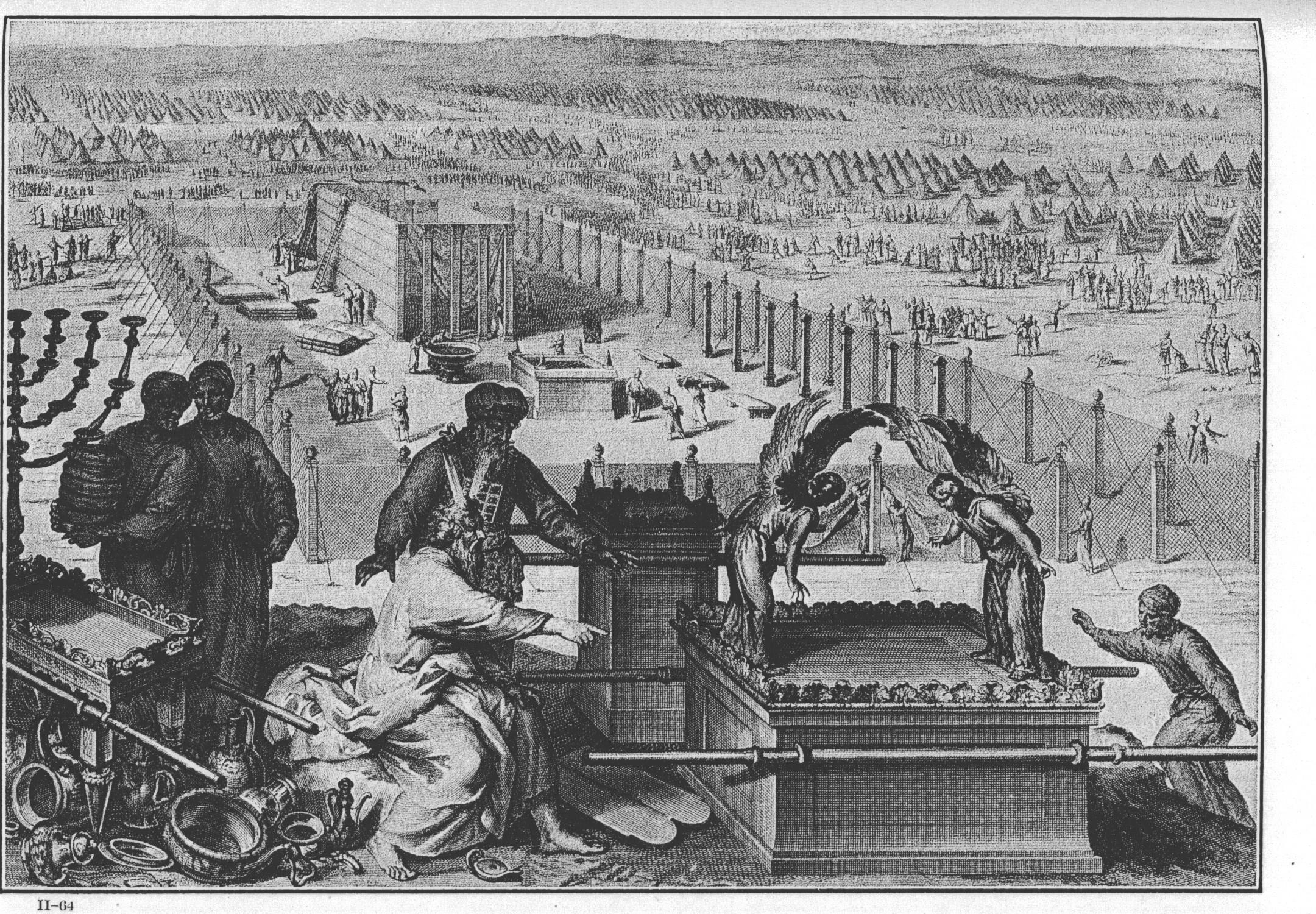

An illustration of assembling the Tabernacle and Sacred Vessels in Figures de la Bible, published in France in 1727 – Photo: Wikipedia

I have to thank the Tabernacle Experience for helping me better imagine how meaningful the temple rituals of ancient Israel might have been to those who practiced them. The re-enactment made the words of Exodus 25-27 become flesh – or, in this case, canvas, wood, metal, and plastic. I felt closer to God when I symbolically placed an atoning sacrifice to burn on the horned altar, and trembled as I stepped through the curtain into the holy of holies. At some points it even felt like attending a service at my Episcopal church. No bells, but definitely smells. And as a Christian, I felt I had grown closer to Jesus, who frequented the temple and would have been familiar with its rituals.

Cognitive Dissonance in the Explanation

Apart from the physical elements of the tour, there was also an audio tour, given by an iPod docent. This “docent” gave me a strong dose of cognitive dissonance. Even as I found a close connection with God through the re-enacted rituals, the audio tour interpreted everything I did in a Christological lens. It implied that these profound rituals were only deficient foreshadowings of the Jesus to come.

One issue that Jewish-Christian dialogue has been confronting for several decades is supersessionism. According to Catholic theologian Mary Boys, supersessionism is the belief that “Christians have replaced the Jews as God’s people because of the Jews’ rejection of Jesus Christ” (Has God Only One Blessing?, p. 7). Supersessionism not only states that Jesus is the fulfillment of the Jewish religion – a point on which Jews and Christians can amicably disagree – but that God has forsaken the Jews. Scholars such as Boys argue that the New Testament sends a mixed message on supersessionism. They trace the painful persecution of Jews throughout Western history supported by this theological belief.

When it comes to scripture, supersessionism teaches that not only are Jewish readings of Scripture reinterpreted in light of Christ, but that those readings are wholly replaced by the Christian message. In this Christological lens on the Torah, the lights of the menorah became the Light of Christ. The sacrifice on the horned altar became Jesus’ atoning sacrifice on the cross. While I felt the curtain between the holy and the most holy place was a meaningful part of the experience, the audio tour told me the opposite. The curtain was not a ritual separation of levels of sacred space to heighten the experience of God’s majesty and transcendence. Instead, the curtain was a wall between humans and God, a wall broken down by Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. This dissonance continued throughout the tour. The smells, sights, and rites of the Tabernacle spoke of the depth of ancient Israelite worship. But the sound of my iPod companion made it clear that I was only to appreciate this makeshift Temple as an incomplete prefigurement to Jesus.

Sometimes the audio tour spoke supersessionism far more explicitly. At one point it described the shift from Temple to Jesus, from old covenant to new, as a shift “from law to love” and “from ritual to relationship.” These old canards paint Jews in Jesus’ time—and, indirectly, our own time—as mired in law and ritual, and as bereft of love for and relationship with God. But they do not match the reality of Jewish faith in either the first or the twenty-first centuries

So I left the Tabernacle Experience feeling ambivalent. I felt an encounter with God and I deepened my appreciation for the worship of ancient Israel. But at the same time, I didn’t care for the supersessionist lens placed on that worship. This Tabernacle was a physical instantiation of some of today’s toughest questions facing Jewish-Christian dialogue around sacred scriptures: How do we recognize the continuing validity of both Jewish and Christian ways of reading the Bible? How do we articulate the Jewishness of Christianity while still acknowledging today’s Jews as fellow people of God?

For me, interfaith dialogue is built on relationship. It’s not something one can do solely in books. So the best way to engage with Jewish ways of reading their Bible is by, well, reading the Bible with Jews. As a student of the Bible in the multireligious setting of the Graduate Theological Union, I had the opportunity to do so when studying rabbinic literature with a Jewish professor in a Jewish Studies program. Rather than a deficient or superseded religion – or a strict law without love, as the Tabernacle narrator implied – I found a complex legal, literary, philosophical, folkloric, and even mystical lens on Tanakh. The reverse is also possible. Just as some Christians have found God in their encounter with Judaism, I know of Jews who have come to like Jesus in the New Testament. One who comes to mind is Priscilla Warner, a Jewish woman in dialogue with her Muslim and Christian friends in The Faith Club: A Muslim, A Christian, A Jew–Three Women Search for Understanding.

I have not “solved” the questions above, or figured out every nuance of how the God of all people calls this Christian to love his Jewish neighbor. But I am positive that our ongoing attempt to live out the answers to the questions of Jewish-Christian dialogue can only arise in a community of relationship with our religious neighbors. Only then can we embrace Judaism not as an outdated set of rituals in an ancient text, but as a living and diverse tradition today.