Freedom at the Fringes

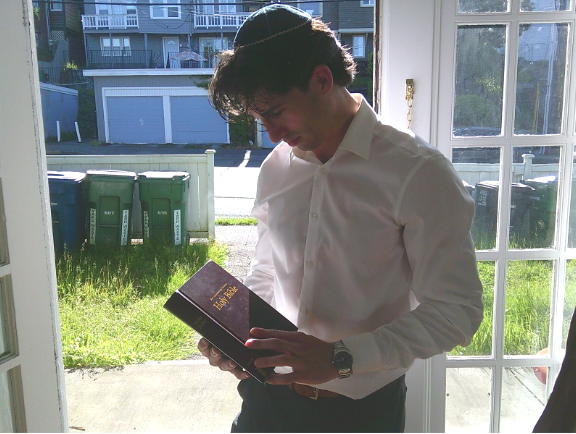

by Ivan Shneerson

I have long struggled to figure out where I belong.

This came to a head during my senior year of college when I, an agnostic and low-observant Jew, chose to live in a Christian living community. Forty-nine young Christian men and me.

Growing up, my family was part of an Orthodox Jewish community. But under Jewish law, Jewishness follows matrilineal descent. Since my maternal grandmother was not Jewish, in the eyes of many, neither was I.

In my new living arrangement, the ambiguity of my identity now confronted me daily. On Friday mornings, I would sit at the long kitchen table for ‘Breakfast & Bible’, where my new Christian brothers cooked and led us through Bible study. That same evening, I would walk down the street to the Rabbi’s home for Shabbat dinner, reciting Hebrew prayers, singing Shalom Aleichem, and gathering over a meal with Jewish friends. Each week, I crossed back and forth between two worlds, welcomed in both but never quite at home in either.

Where, then, did I belong?

Explorations in interfaith

When I thought of belonging, I imagined there being a circle with a secure center, a bullseye, where the “real” members of a group resided. Those people shared the same beliefs, customs, and convictions. Some people would orbit closely, while others were far out on the edges.

From my vantage point, the “center” of any community looked like the prize; that place where everyone was in agreement on key ideas and everyone there belonged. If only I liked what they liked, believed what they believed, checked the right boxes, then I would fully belong, I thought.

In the Christian community, there were a few young men I encountered that seemed to truly embody the bullseye. They were admired as men of strong faith and leaders in the community. They interpreted scripture literally, prayed with conviction, and rarely voiced doubt.

I was not like them. Our discussions of faith, Scripture, and theology felt more like debate than dialogue, and I wondered whether I could ever fully belong to a group whose central members had interpretations of belief that felt so different from my own.

Yet the more we talked, the more I wondered if their certainty was something to long for. If every Biblical verse had to be taken without question and every belief had to remain airtight, there was no room to admit even the smallest hesitation or alternative interpretation. While their convictions were strong, their beliefs seemed to carry an odd fragility, as if the whole structure might collapse like a house of cards with the admission of a single doubt. Their centrality seemed less like freedom and more like confinement.

The more time I spent among people who seemed to live at the center, the less certain I became that such a place truly existed. The center, I came to realize, is constantly moving, a horizon that recedes no matter how long you walk towards it. The center is a mirage.

Desert mirage

To cling to it is to chain oneself to a moment, or a specific and static set of ideas, and in the process, give up the freedom to grow with new information, to learn. In truth, we are all constantly orbiting around a central set of beliefs and ideas, sometimes growing closer, only to realize that the target seems to shift, and we are once again further away. I believe that in taking our faith seriously, we will see that it ebbs and flows with life events, things we learn, and people we meet.

Even those who seem fully ‘in’ often carry doubts, but never voice them. A devout believer may question a verse and keep silent. A political loyalist may privately disagree with a key policy and never admit it. The circle of certainty is far less solid than it appears.

I have found a unique kind of freedom in sitting in a space of ‘I don’t know’ with a curiosity and openness to others’ beliefs, dwelling between groups, identities, and ideas. Maybe, where I belong is in between.

I have since graduated from the Christian community, and soon I will move into a new place with close friends I met there. The seven of us hold drastically varying beliefs. I plan to continue participating in a small group shaped by Christian practice that is open to personal flair and perspective. Some Sundays I will go to church. Other weeks, I may sit in Buddhist meditation or simply hike in the quiet of nature. I will continue to look for Jewish spaces where I feel fully accepted for my unique identity.

The importance of being comfortable with the in-between extends far beyond my own spiritual life. If more of us could hold space at the edges, allow room for quiet doubts, and understand that perfect conformity is not a goal to strive for, we may create more room for honest dialogue in our political spheres, religious circles, and communities at large. That space might allow ideas of tremendous impact to emerge from just beyond our fingertips.

To those who also live at the fringes, I encourage you to see it not as exile, but as opportunity. You may feel that you do not belong fully anywhere, but you may also belong, in some way, everywhere. In embracing your liminality, you may be open to new ideas, opportunities, and possibilities. Maybe that is the truest freedom of all.