Ruth Broyde Sharone

Growing the Interfaith Community

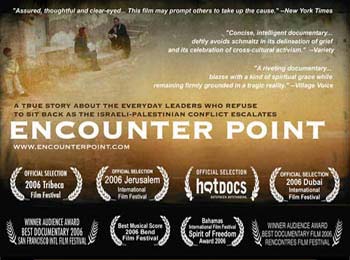

Encounter Point and Budrus, two films produced in Israel by Just Vision’s resourceful executive director, Ronit Avni, exemplify what documentary film does at its best: raise public consciousness and inspire people to change.

In both films, Israelis and Palestinians, Muslims, Christians and Jews, are inspired to seek alternatives to the hardened “status quo” of the Middle East conflict. Encounter Point, released in 2006, affords an up-close-and-personal look at Israelis and Palestinians suffering enormous personal losses brought on by violence and terrorism. In spite of a hostile political climate and logistic challenges, Israeli and Palestinian parents who have lost children to war begin meeting with one another to grieve together. As Leonard Cohen reminds us in his song Anthem, “Ring the bells that still ring…forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

Within the crack of their shared grief, both sides begin to talk, to see each other as brothers and sisters, victims of war, not enemies. We observe families from both sides becoming close friends in spite of criticism from their families and communities. But when segments of the movie are shown to their families and those who never considered “talking to the enemy,” it becomes clear that hard-liners can be influenced to modify their views. The documentary was screened around the world. Participants traveled with it in interfaith pairs, Muslim and Jew, discussing the powerful impact of the film when it was shown on the home front to Palestinians and Israelis.

More recently, Budrus, directed by Brazilian-born filmmaker Julia Bacha, shows how residents of a Palestinian village slowly adopt non-violent tactics to achieve a victory against Israeli army bulldozers threatening their land and livelihood because of the wall being constructed to protect Israelis from Palestinian terrorism.

Iltezam Morrar, a leader in Budrus. Photo: Just Vision

A fifteen-year old Muslim girl, Iltezam Morrar, becomes a heroine in her own village and a Joan of Arc for Muslim women around the world. The daughter of the resistance leader in the village of Budrus, she first appears to be an adolescent. By the end of the film we see her as an articulate young woman with remarkable leadership abilities. The film dramatically turns the spotlight simultaneously on non-violent protest and the unleashed potential of women in the Middle East!

The film was screened widely in the West and in many Arab countries, garnering awards and significant media attention. In an article published in the New York Times in 2010, journalist Ethan Bronner wrote:

“Budrus,” however, is not just the story of its surprising principals playing out gritty real-time confrontations. It raises some of the most difficult and contested questions surrounding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, notably the ability of each side to understand the other and the role of popular, nonviolent struggle in bringing it to an end. The film itself has become a part of that debate: it is now being shown in villages and towns in the West Bank to spur Palestinians to embrace nonviolence.

Filmmaking and Interfaith Activism

More than 35 years ago I became a documentary filmmaker. I had had high aspirations as a script supervisor and assistant producer for four feature films, working in the U.S. and Israel. But while filming in Israel I felt an urgency to become a documentary filmmaker, not only because I love the medium, but because I believe documentaries can be a potent catalyst and provocateur for change.

That conviction led me to make God and Allah Need to Talk in 2003. Two years after the horrific events of 9/11 I spotted a billboard in Hollywood that proclaimed, “God and Allah Need to Talk.” Knowing that God and Allah were just different names for the Divine, that billboard continued to haunt me for days afterwards. It indicated that we not only had divided ourselves since 9/11. We had divided God as well.

Eager to document efforts for reconciliation and healing, I received permission to film a Muslim-Jewish Seder in Woodland Hills, California, initiated by courageous Jews and Muslims from around the city. The organizers’ goal was to end the silence between Ishmael and Isaac, so they named the event “A Seder for Reconciliation” and held it during Passover.

The following year, Christians from All Saints Church of Pasadena were inspired to help their Muslim and Jewish brothers and sisters organize an even larger, more inclusive Seder — demonstrating the exponential possibilities of interfaith engagement. Those events formed the spine of my documentary titled God and Allah Need to Talk.

I have shown the film around the country on college campuses, in synagogues, churches, mosques, and community centers. It has been screened internationally and translated into Spanish. A year ago I was invited to show the film and lead an interactive discussion with the participants of an interfaith organization in Pomona, California. Inspired by the interfaith Seder they saw in the film, they decided to organize their own in Pomona.

For six weeks, for an hour or two a week, I coached them on the phone, discussing the fine points of putting together an interfaith event that could potentially include all the diverse religious communities in their area. They formed committees and worked long hours to insure its success. In a break with tradition, the local Pomona mosque, rather than a synagogue, hosted the Seder, one of the first Seders ever held in a mosque in this country.

Iltezam Morrar, a leader in Budrus. Photo: Just Vision

More than 250 participated. Overflowing the mosque’s outdoor patio, they spilled into the parking lot. More tables and chairs were located at the last minute to accommodate everyone. At each table participants read aloud a part of the Haggadah, which tells the story of the ancient Israelites’ liberation from oppression and asks those present to consider who are the Pharaoh and Moses in their own lives. Many individuals attending from the neighborhood had never met a Muslim before – I know because I interviewed them. They were excited and curious and had an opportunity to view Muslims performing their afternoon prayers in the sanctuary, an unexpected interfaith bonus.

The Seder was so successful the Pomona interfaith community held another one this year, again in the mosque, and jubilantly announced that it will be an annual tradition. The local Pomona newspaper covered it, in itself a triumph since reporters tend not to show up for the good news.

We owe a great debt to the new breed of documentary filmmakers taking on the tough issues – health, food, war, corruption, trafficking, the environment, and so much more. Even the Oscars are paying more attention to documentaries, as are filmgoers. Interfaith relationships figure prominently in many of these productions, since living in an unbelievably pluralistic world is part of everyone’s story today. It is clear that documentaries can offer a way to change how people perceive major issues troubling the world and inspire individuals to serve as catalysts for peace.

Don’t ask how difficult it is to finance these documentaries, but know that this is a sweet moment for those of us who have chosen the documentary to highlight the rise and spread of interfaith outreach around the globe.

Ruth Broyde Sharone’s new book Minefields & Miracles: Why God and Allah Need to Talk is reviewed in this issue.