By Marcus Braybrooke

Key Figures in Interfaith History

The 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago is often regarded as the birth of the interfaith movement. But whose idea was it? The answer is Charles Carroll Bonney.

In the late eighteen-eighties public discussion began about how best to mark the 400th anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of America by Christopher Columbus. The consensus was to hold a giant exposition of “the arts, industries, manufactures and the products of soil, mine and sea.” That, for Charles Bonney, was not enough. “Something higher and nobler is demanded by the enlightened and progressive spirit of the age.” Writing in 1889, Bonney suggested in addition “a parliament of nations” bringing together leading “statesmen, jurists, financiers, scientists and theologians” from across the world.

At that date the Exposition venue had not been decided, but Chicago was one of the cities in the running, and its provisional committee welcomed the idea. By 1890 the Chicago planning committee – having defeated bids from New York, St. Louis, and Washington DC – agreed that the World’s Congress Auxiliary should be an official part of the World’s Columbian Exposition, which chose as its motto “Not Things, but Men.” Bonney was appointed President of the Auxilary, but instead of his proposal for a multi-disciplinary congress, it was decided to have a series of congresses – in fact more than 200 – on different subjects. To Bonney, religion was the most important. Whereas the Exposition was at the ‘White City’ in Jackson Park, the congresses were held at Chicago’s Art Institute – used again in 1993 for the Parliament’s centennial celebration.

Charles Carroll Bonney

Bonney quickly appointed a sixteen-member committee to plan the Religious Congresses – both the World’s Parliament of Religions and numerous denominational congresses. Bonney later said that he faced his first meeting with the religious congresses committee with ‘much anxiety.’ We do not know why. Did he fear that its members – all Christians except for one rabbi – would reject his plan that all religions should be represented?

To his delight, the committee welcomed Bonney’s suggestion that the Parliament would “unite all religion against all irreligion, make the Golden Rule the basis of this union, and present to the world... the substantial unity of many religions in the good deeds of the religious life.” It was, of course, the participation of leaders of several religions which gave to the gathering its lasting importance. The detailed implementation of this great plan was in the hands of John Henry Barrow – of whom more in a subsequent issue.

Religion was not Bonney’s only interest. Born in Hamilton, New York on September 4, 1831, Bonney attended Colgate University and received his LL.D. He then moved to Peoria, Illinois, where he founded a school and helped set up the state’s school system. Bonney moved to Chicago in 1860 and became a judge in Supreme Court of Illinois. Subsequently many journalists thought he should have been made a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Bonney was one of the founders of the International Law and Order League, which paved the way for the International Court of Justice in the Hague.

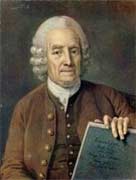

Emanuel Swedenborg

Bonney himself was inspired by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), a Swedish scientist, philosopher and theologian and prolific author. Swedenborg summarized his thinking in Vera Christiana Religio, published in 1781, when he was 83. The being of the Lord, Swedenborg said, cannot be described, but the Lord’s essence can be perceived in the primary qualities of love and wisdom. This approach suggested a mystical truth beyond creedal formulae. As Bonney said, “every nation has some religion,” and there are “common essentials of all religions, by which every one may be saved.”

For Bonney religion meant “love and worship of God and love and service of others,” which he claimed could be found in every religion. “There is an influx from God into the mind of every man,” he said, echoing the words of St. John’s Gospel that “the true light lighteth every person who comes into the world.” Just as sunlight is received differently by different objects, so Bonney said, divine light is received differently in the minds of men and “hence arise the various forms of religion.” This did not mean he regarded all religions as equal, but insisted that others should have the same freedom of belief that he claimed for himself.

Swedenborg himself did not found a church, but in 1817 some of his followers established the New Jerusalem Church, which Bonney joined. Indeed, he claimed that “the whole plan of the religious congress” rested upon the fundamental truths that he had learned in the New Jerusalem Church and that these truths made the Parliament of Religions possible.

Bonney, after a period of illness, died ten years after the Parliament. He regarded his presidency of the World’s Congress Auxiliary as the greatest accomplishment of his career. To him, the Parliament of Religions was “the culminating achievement of the whole series of congresses’ and the “crowning event” of the exposition.

Indeed, what else of all the celebration in 1893 is still remembered today?