Excerpts from Interfaith Leadership: A Primer

By Eboo Patel

WHAT IT TAKES TO BE AN INTERFAITH LEADER

Below are excerpts from the opening and closing of the Introduction to Interfaith Leadership: A Primer, a new book from Eboo Patel being published by Beacon Press this August. Copyright by Eboo Patel.

* * *

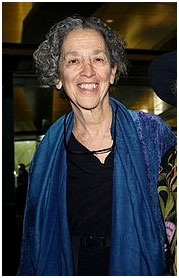

What Is Interfaith Leadership? Ruth Messinger, the former president of the American Jewish World Service, has a powerful story of interfaith leadership. She grew up in an observant Jewish home in New York City, attended Radcliffe College in the early 1960s, married, and started seeking a way for her (then) husband to avoid the Vietnam War. His best option was finding work as a doctor in a government facility. They tried getting a position in a major city on one of the coasts, but somehow wound up being assigned to a small town in Oklahoma. Ruth decided to make the most of an unfamiliar situation and enrolled in the master’s program in social work at the University of Oklahoma.

Ruth Messinger – Photo: Wikipedia

After completing her degree in 1964, Ruth took a job as the director of child welfare programs for two counties in western Oklahoma. She quickly discovered that what passed for children’s services in the area was an ugly collusion between the sheriff and Ms. Lucy, a woman who ran a ramshackle orphanage. Children and teenagers caught running away from home or committing minor crimes were thrown into jail and then sent to Ms. Lucy’s orphanage. Ruth’s first order of business was to inform the sheriff that putting a minor into jail was illegal. Moreover, Ms. Lucy’s “facility” was totally unfit for children. If the minor’s family was indeed unsuitable, the state had to provide an appropriate foster home for the child.

The sheriff’s quick retort was that there were no foster homes in the area, and thus his was the only game in town. Then he lit into Ruth. She was clearly not from around here, she was a woman, and – to top it all off – she was Jewish. She could go take a hike.

Ruth knew that part of what the sheriff was saying was true; there were no foster homes in the area for the youth who needed them. Her job was not just to end the terrible current practice; it was to create a better alternative. She started going for walks around various neighborhoods in her town to get to know the area better, pushing a stroller with her newborn baby inside. She noticed that many of the private residences were marked with religious signs like “The Church of Jesus Christ Who Died for Our Sins.”

Ruth knocked on doors and began conversations with the people who answered. She introduced herself and explained that her job was to help vulnerable children in western Oklahoma. She detailed the challenges facing troubled youth in the area and expressed that her highest hope was to help those kids find loving homes. Based on the religious sign she had seen outside the house, it looked like the residence doubled as a place for worship and community gathering. Might they help? The most common response went something like this: “Come back on Wednesday morning for our praise service and speak to the group.” There seemed to be some kind of religious gathering taking place at one house-church or another just about every day of the week and just about every hour of the day. Ruth sat through countless sermons, praise songs, and altar calls. As promised, the preacher would give her a chance to speak. Ruth would rise and tell stories of local children and teenagers in need. When she was done, the preacher would quote scripture and say to the gathered worshippers, “Who here will answer the call of God and serve as loving families for these young people?” “People would literally line up to help,” Ruth said. “It was amazing to witness. Those evangelical house-churches built the child welfare network in western Oklahoma.”

I found one particular story that Ruth told especially moving. Every few weeks or so, Ruth would get a call from the sheriff in the middle of the night. As the number of foster families in the area grew, he had grudgingly stopped his practice of throwing troubled youth in jail and carting them off to Ms. Lucy’s facility. Instead, when he caught a runaway in the middle of the night, he phoned Ruth. “If you can’t find a home for this kid within the hour, she’s going to jail,” he would say in his gruff voice. Without getting out of bed, Ruth would phone her friend Stacy, a devout evangelical who had told Ruth that she felt called by God to do whatever she could to help youth in need. Ruth would explain the situation, and Stacy would say, “Have the sheriff drop the girl off at my house.” Ruth relayed the message to the sheriff. Stacy would meet the child at the door with a cup of hot cocoa, make her feel comfortable, and give her a bed for the night. Ruth would show up the next morning to work out a long-term solution.

Ruth Messinger (on the l.), marching in the 2015 New York Pride Parade – Photograph: Twitter

Even as things got better, they were far from easy. Part of this had to do with Ruth’s being Jewish in a time and place rife with anti-Semitism. Ruth recalls riding in a car with a group of older women when one of them said that she was off to do her shopping and aimed to “Jew down” the prices. She also remembers the day her colleagues at work found out that she was Jewish. She was met with surprised looks and a comment from her boss: “Well, you don’t look Jewish.” Many of the things that she heard in local churches contradicted her faith; some even offended her. One time, she was invited to a Sunday morning service at one of the fancier churches in town. It turned out to be Palm Sunday, and the pastor gave a fiery sermon on the killing of Jesus – by Jews.

Ruth was deeply offended and resolved to use the moment as an opportunity for education. She invited the pastor over to her home for tea and what we would now call an interfaith conversation. Ruth shared that not only was the pastor factually wrong about his claim that Jews killed Jesus, but that she was Jewish and felt hurt and insulted by his sermon. Moreover, America was growing increasingly religiously diverse. Sermons like the one he just gave were sure to cause division. And then Ruth pointed out a powerful area of commonality between her faith and his: Jesus was Jewish. Instead of preaching insulting and divisive falsehoods, why not focus on how the actions of Jesus inspired both Jews and Christians to serve others?

Just as Ruth helped the Christians she worked with understand Judaism, so she developed a deeper appreciation for evangelical Christianity during her time in western Oklahoma. She was especially struck by the ethic of service in the community: “They preached that God meant for us to serve others, and they practiced what they preached. When the pastor asked for volunteers and quoted scripture, people lined up to help.” The 1960s were a tumultuous time – the women’s movement, the counterculture, the protests against the Vietnam War. Ruth Messinger and those evangelicals in western Oklahoma lined up on different sides of most of those major issues. Ruth was a graduate school-educated liberal Jewish feminist from New York who found herself in Oklahoma because her husband was fleeing the Vietnam War. The evangelicals she was working with helped make Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee,” with its lyrics celebrating a traditional understanding of American patriotism (against draft-dodging; for waving the flag on Main Street), one of the most popular songs of the era. Suffice it to say there were significant differences between Ruth and the majority of her evangelical partners on most of the issues of the time.

Yet Ruth identified a powerful point of intersection between their evangelical Christian values and her Jewish values. At the heart of that intersection was the welfare of young people from troubled family situations in western Oklahoma. There are hundreds in western Oklahoma who lived in loving homes rather than a derelict orphanage because of Ruth.

Exemplifying Interfaith Leadership

Ruth’s story exemplifies the kind of interfaith leadership I focus on in this book. Interfaith leaders are people who have the ability to lead individuals and communities that orient around religion differently toward understanding and cooperation. This book makes a case for why this work is important and provides a guide for how to do it effectively. To that end, it is useful to say a few more words about how Ruth’s story illustrates this kind of interfaith leadership.

Ruth sought connection rather than division. When she saw Christian signs outside of people’s homes, her instinct was not “I disagree with that understanding of Jesus, therefore I am staying away from that house.” Instead, she thought to herself, “That is clearly a place where a leader lives and people gather. I will certainly have differences and disagreements with them, but we will also likely have some deeply held values in common. I will work to find those shared values and highlight them in a way that inspires all of us to create a foster-care network for youth.”

It is one thing to seek connection; it is another thing to have the skills to successfully connect. Ruth found ways to speak to and mobilize a different religious community for a common cause. She learned to build trust with the pastor. She learned to earn goodwill by paying personal visits to house-churches and spending time with the people who gathered there. She even learned that being a new mother with a little baby provided an initial point of positive contact.

Ruth had significant disagreements with her evangelical partners. She did not agree with them about their doctrine of Jesus as Lord and Savior, or their support for the Vietnam War, or their dim view of feminism. Ruth did not attempt to erase those disagreements, nor did she let the disagreements prevent her from partnering with them on finding foster homes. When the disagreement crossed the line into insult, she addressed the situation head-on, as with the Palm Sunday sermon on Jews killing Jesus. Crucially, she used the situation as an opportunity to educate her interlocutor, not simply scold him. Her method of education was to highlight something shared between their different traditions, namely, that Jesus was Jewish.

Even as Ruth was educating those around her about Judaism, her own knowledge about and appreciation for evangelical Christians grew. She admired their strong sense of community and their deep belief in God and, most of all, that they preached the importance of service and practiced what they preached...

* * *

This book has seven chapters, corresponding to the six categories that I think are essential for interfaith leadership: identity, theory (this category has two chapters), vision, knowledge base, skill set, and intangible qualities.

A youth leadership summit in Washington, DC, last year, sponsored by the Interfaith Youth Core – Photograph: Interfaith Conference of Metropolitan Washington.

Chapter 1, “The Identity of an Interfaith Leader,” explores how people can mine personal experience to create a narrative identity as an interfaith leader.

Chapters 2 and 3 are about the theory of interfaith. I break the term “interfaith” into its component parts, “inter” and “faith.” “Inter” is defined as the relationships between people who orient around religion differently. “Faith” is defined as the relationship between an individual and what we commonly understand as a religious or philosophical tradition (such as Christianity, Hinduism, or humanism). The term “interfaith,” therefore, has two profound implications: how do our relationships with those who are different affect our relationships with our religious or philosophical traditions, and how do relationships with our traditions affect how we interact with people who are different from us.

Chapter 4, “The Vision of Interfaith Leadership,” presents frameworks that flesh out what interfaith leaders hope their efforts will achieve.

Chapter 5 is on the knowledge base required for interfaith leadership.

Chapter 6 enumerates the skill set needed to be an effective interfaith leader.

Chapter 7 highlights the intangible qualities that separate truly exceptional interfaith leaders from merely good ones. The conclusion summarizes the main themes of the book in the context of a concrete example.

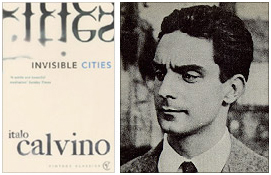

Interfaith work is often referred to as bridge building. My favorite bridge is a literary one, from Italo Calvino’s beautiful book Invisible Cities. In one chapter, the traveler Marco Polo describes to the emperor Kublai Khan a particular bridge in his kingdom. The emperor grows impatient and asks Polo to get to the point. He wants to know about the stone that holds the bridge together.

The bridge is not held together by a stone, says Polo, it is held together by an arch.

So tell me about the arch, says the Emperor.

Without stones, retorts the traveler, there is no arch.

Polo’s bridge is the guiding metaphor for this book. As you read through, I hope you come to view yourself as a bridge builder (identity), develop an understanding of the complex landscape you are building on (theory), get a clear image of the destination you are building toward (vision), acquire the stones that are the main materials of the bridge (knowledge base), build the aptitude to connect the stones into an arch strong enough to hold a diverse community (skill set), and cultivate the intangibles that give people enough confidence in your leadership to risk the journey (qualities).

Header Photo: J. Trotter