By Paul Chaffee

THE 'UNAFFILIATED' STEP FORWARD

The Pew Forum’s October 9 report on religion in America was released in the midst of a presidential campaign in overdrive, daily doses of bad-news business stories, violence in Syria and the threat of violence in Iran. Nevertheless, on October 9 the New York Times noticed what looks to be the biggest religion story of 2012, as did the Washington Post, CNN, Huffington Post, and dozens of other news outlets.

Titled “Nones” on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have No Religious Affiliation, the Pew report notes a radical shift in the religious landscape:

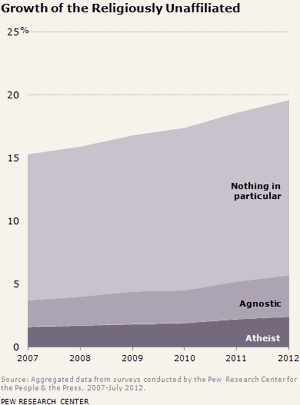

In the last five years alone, the unaffiliated have increased from just over 15% to just under 20% of all U.S. adults. Their ranks now include more than 13 million self-described atheists and agnostics (nearly 6% of the U.S. public), as well as nearly 33 million people who say they have no particular religious affiliation (14%).

Forty-three million religiously unaffiliated adults is a huge constituency. The number has been going up a percentage point a year. This suggests that five years from now, the religiously unaffiliated will include more than 54 million, a likely scenario, since among the under-30s today, the religiously unaffiliated percentage is 30 percent, not 20. And this year, Pew notes, Protestant Christian adults in the United States, in the aggregate, total 48 million, down five million in five years; the unprecedented loss is largely among white Protestants. Ethnic Christian numbers have remained stable. In yet another RNS story, Kimberly Winston notes that “nones” made up 12 percent of this election, “only slightly smaller than the combined number of Hispanic Catholics and Black Protestants (14 percent).” Moreover, “The nones also skewed heavily Democratic, 70 to 26 percent.”

Spiritual but Not Religious

The 33 million unaffiliated who do not self-identify as agnostic or atheist tend to represent an “I’m spiritual, but not religious” (SBNR) perspective. A variation on the theme claims, “I’m a follower of Jesus, but don’t call me a Christian.” Anti-establishment notions like these have been batted around religious circles for several years. YouTube took it viral, which generated lots of heat online and in religious establishments. The most insightful response, Philip Clayton’s “Letting Doubters in the Door” last March in the L.A. Times, was the exception. The dominant theme with most religious pundits and leaders – SBNR is light-weight, self-centered and selfish, which may be understandable but is misguided.

“Nones” on the Rise from Pew has snapped everyone to attention. The response this past month from religious leaders and bloggers has been more reflective, measured, and significantly larger. Religious News Service (RNS) published an excellent summary a day before the report was released, and editorials and pundits started asking, “Why are so many saying no to institutional religion?”

Taking the Matter Seriously

Graphic: SBNR.org

Theologian Brian McLaren observed in the Huffington Post, “Christianity has carried on a long affair with empire and colonialism, and as a result, has picked up the imperial auto-immune disease of ‘hostility to the other’.” Students have told McLaren, “People don’t want to have to side with the church and against their friends who are Buddhist or Muslim or Jewish or agnostic.”

In a follow-up story about the report, RNS queried 23 religious leaders about the findings. They represented Buddhist, Catholic, Hindu, Humanist, Jewish, Muslim, and Protestant perspectives.

Institutional mea culpa surfaces repeatedly. Rabbi Arthur Green suggests that “Young people… see organized religion too caught up in the past, fighting the last century’s battles, blind and deaf to the needs of an ever so rapidly approaching and potentially calamitous future.” Jesuit James Martin confesses that “Sadly, many young people tell me that even if they believe in God, they find organized religion not only boring and irrelevant, but corrupt and offensive.”

Presbyterian pastor Bruce Reyes-Chow’s analysis of “why the Protestant church has lost a generation” unpacks three judgments: “We have failed to relinquish power… We have dismissed the complexity of a generation… We have commodified a generation.”

At the same time, hope abounds about institutional religion’s ability to renew its relationship with those who have left or were never there in the first place. Harvard Humanist chaplain Chris Stedman says, “The fact that 80 percent of the religiously unaffiliated surveyed think that religious organizations and communities play a positive role in society suggests to me that there is a real opportunity today to build greater understanding and cooperation between the religious and nonreligious.”

Bill Aiken of the Soka Gakki Buddhists notes, “Our strength has been in the monthly discussion meeting, a neighborhood gathering of 10-20 people in someone’s home. The format is informal and the communication is horizontal, based on the sharing of experiences, not the vertical communication of preaching or teaching.”

Samuel Rodriguez, Evangelical pastor and Hispanic leader, writes, “This generation does not question the validity of the wine. This generation repudiates the idea of wineskins that lack transparency, authenticity and relationship.” And Muslim interfaith activist Eboo Patel puts the challenge to us all: “There are people out there saying faith is an injection of poison or a bomb of destruction. We have to emphasize that it’s the beating heart of significant social movements and a bridge of cooperation.”

If the RNS stories leave you wanting more, Wayne Slader’s blog for the Dallas News adds another dozen voices, Texas religious leaders from different traditions. The discussion will continue for years. Books will be written about what Sarah Posner in Religion Dispatches last week called the “great religious realignment,” particularly about its political ramifications.

Three-quarters of the religiously unaffiliated favor Democrats over Republicans, one of several tough issues the GOP will be examining during Barack Obama’s second term. Obama won 70 percent of the religiously unaffiliated vote, according to CNN exit polls. Other countries will be having similar discussions. Eleven days following the Pew report, Ireland’s Irish Times published “People ‘with no religion’ on the rise.”

For Christians, perhaps the most important work building on spiritual community in America is Diana Butler Bass’ Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening (2012). Bass, while controversial, has a distinguished career as a passionately engaged scholar of congregations. In response to the realities conveyed in the Pew Report, her work is imaginative and inspiring, and not just for Christians.

Diana Butler Bass

The best current discussion of SBNR on the web is Bass’ 15-minute video interview posted by Religion & Ethics Newsweekly on October 26. It is full of insight and hope, and she leans into the culture’s growing interfaith interaction to exemplify what is happening to religion in America and how to respond faithfully, whatever your tradition.

Equally provocative is another Philip Clayton piece, “The Nones: Skeptics Are the New Religious” in Sojourners, with insights that take the discussion another mile down the pike.

Challenging the Interfaith Movement

This same realignment in America’s religious identity, in fact, will force the interfaith movement to reconsider who it is and how it wants to operate. An interfaith axiom for a quarter-century has been that we are building bridges of friendship and collaboration, not creating new religion(s). But how do you respond to the person who says, “I grew up without any faith connections, but I’m on a spiritual quest. My friends and I engage in all sorts of spiritual ceremony and ritual. And I’d like to sit down at the interfaith table – is there a place for me?”

Young adult interfaith groups in recent years have thrown open their doors to such seekers, welcoming self-identifying atheists and agnostics as well, who want to participate in the collaborative community’s quest to ‘heal the world.’ Similarly, sexual identity differences make no difference in these communities – all are welcome.

As time goes by, new relationships will develop between religions and emerging groups like interfaith seminaries and social networks like SBNR.org, which draws 50,000 website visits a month these days. Many seekers will become involved in new spiritual communities and explore “interspirituality” as presented in books like The Coming Interspiritual Age, published this month and reviewed in these pages. Like the Soka Gakkai Buddhists, people are creating new ways to organize community, faith, and spiritual practice. In the end, what seems like a loss may be a source of enrichment for the whole human family.