By Rabbi Rami Shapiro

FINDING COMMON GROUND

Everything I need to know I learned on a zafu.* The year was 1967. I was 16 years old, and had been studying Zen Buddhism and sitting zazen for a few months when I had what one might call a mini-kensho experience. An awakening. Sitting by the shore of a lake in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, my body/mind fell away, and I knew — nothing. When the body/mind is gone, so is the distinction between subject and object, and with that loss one loses the capacity for knowing since knowing requires an object to be known and a subject to know it. When my body/mind returned, however, I found myself laughing wildly, in love with and loved by all things, and certain in a way I have never been certain before or since of the absolute nonduality of all reality.

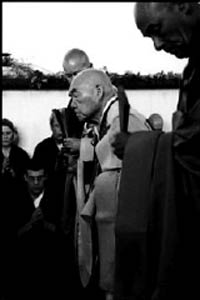

Kyozan Joshu Sasaki in 2007 – Photo: Wikipedia

At the time I ascribed this experience to Zen and devoted the next ten years of my life to that practice, thinking I could in this way regain this “experience.” I studied Zen with Taitetsu Unno at Smith College, and under the guidance of Sasaki Roshi and Gesshin Myoko Prabhasa Dharma Roshi. Early on in my practice Sasaki Roshi urged me to abandon my plans to pursue an academic career in Buddhist Studies, and to move to his center on Mount Baldy instead. Surprised — horrified? — by his suggestion, I blurted out, “I can’t do that, Roshi, I’m going to be a rabbi.” This was news to us both.

“Be rabbi,” Roshi said to me, “be Zen rabbi!”

I’m not certain what a Zen rabbi is, or if I am one. But I did gravitate to those Jewish teachers, teachings, and techniques that seemed congruent with my understanding and practice of Zen.

There was one problem: I kept running into God.

True, I have no interest in mainstream Judaism’s dualistic theology and self-conscious deity, but I couldn’t abandon God-language altogether — after all even a Zen rabbi is still a rabbi — and therefore had to find a way to understand God that fit my nondualistic view of reality. Enter Advaita Vedanta. I became a student of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda; and found Ramana Maharshi’s wisdom and practice of Self-Inquiry even more compelling that zazen.

As my understanding of Vedanta deepened, largely under the tutelage of my friend Swami Atmarupananda, I reawakened to the Advaita Judaism of the early followers of the Baal Shem Tov, the 18th century founder of Hasidism, that I had studied years earlier. The more I studied the philosophy of rabbis such as Dov Ber (d. 1772) and Schneur Zalman of Liady (1745–1812), the more convinced I became that Advaita was a legitimate strand of Judaism and that I could with very little effort weave the two traditions — Vedanta and Zen — into my own personal Jewish path.

Since these Jewish teachings are so rarely known, let me share several with you:

God is found in all things and all things are found in God… Everything is in God, and God is in everything and beyond everything, and there is nothing beside God. – Moshe Cordovero (1522-1570)

Everything is God who makes everything be, and in truth the world of seemingly separate entities is entirely annulled. – Schneur Zalman of Liady

The absolute reality of God, while extending beyond the conceptual borders of “existence,” also fills the entire expanse of existence as we know it. There is no space possible for any other existences or realities we may identify — the objects of our physical universe, the metaphysical truths we contemplate, our very selves… do not exist in their own reality; they exist only as an extension of divine energy…. – Menachem Mendal Schneerson (1902-1994)

Sri Ramakrishna, a pioneering champion of religious pluralism, was Vivekananda’s teacher. – Photo: Wikipedia

Three years ago, wishing to honor my teacher and his lineage, I asked to be initiated into the Ramakrishna Order of Vedanta Hinduism and was granted this boon by Swami Swahananda, who himself had been initiated by Swami Vijnanananda, a direct disciple of Ramakrishna. In honor of my various lineages, I continue to engage in a variety of daily practices — Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu.

With this as prologue let me answer the question that was the catalyst for this essay: “How do Hinduism and Buddhism influence me as a rabbi?”

They don’t. They are me as a rabbi. You cannot separate me the rabbi from me the student of Advaita; they are one and the same.

Given this admission, a second question arises: “Is my Judaism authentic?” Honestly, I don’t know, and, more importantly, I don’t care.

I love my teachers and do my best to honor what they have taught me, but I don’t pretend to carry their teachings into the world. I love Judaism, and I do my best to honor her wisdom, but I do not pretend to represent any brand name Judaism. I’m a Jew with deep respect for the nondual wherever I encounter it. “Authentic” is beside the point.

What is the point? Truth. I am not one who believes that something can be true if it is true for you, but not for me. If a thing is true, it must be true for everyone, though not everyone need accept it as such. Evolution is true, even though millions of Americans deny it. The Earth circling the sun was no less true during the centuries that the Church denied it, and no more true now that the Church accepts it.

The truths I follow are simple: (1) all life is an expression of a singular, dynamic process I call YHVH (the Hebrew name of God derived from the verb “to be”); (2) realizing this to be true leads to a life devoted to the welfare of all beings: love your neighbor as your self and realize that all neighbors are the Self; and (3) contemplative practices and the study of the teachings of the nondual mystics found in any religion (and beyond religion) are ways to realize the first truth and cultivate the second of these three truths.

While I have no need to defend these truths, and feel no need to convince anyone else of them, I don’t believe they are “true for me.” They are true for everyone. The extent to which Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, or any religion or philosophical system adheres to these truths is the extent to which I take them to be true. The extent to which they negate this truth is the extent to which I take them to be untrue.

I have held this position for 46 years. While I would like to think I’m open-minded enough that, given solid evidence to the contrary, I could change my mind and accept a different truth, I doubt this will ever happen. What I discovered sitting on that zafu on Cape Cod has defined my life and my living. I suspect — indeed hope — it will define my dying as well.

* A zafu is a cushion sat on during Zen Buddhist meditation.