By Marcus Braybrooke

THE LONG JOURNEY IN GETTING TO KNOW EACH OTHER

Prime Minister Cameron’s claim that “Britain is still a Christian country” has sparked a heated debate in the UK. The traditional description of Europe as ‘Christendom’ is also ambiguous. Jewish minorities were often oppressed or exiled, but, as in the Golden Age in Spain, they contributed to European culture. Muslims, who at times ruled parts of Mediaeval Europe, also had an influence, although as during the Crusades, the contact was often adversarial. Even so, Avicenna and Averroes and other Muslim scholars transmitted the teachings of the Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle. The English scholar named Robert of Ketton made the first Latin translation of the Koran in the twelfth century; it was printed in 1543.

Long Before ‘Interfaith’

William Carey – Photo: Wikipedia

From the sixteenth century, colonists and missionaries came into regular contact with people of other faiths. William Carey, one of the first Protestant missionaries to India, translated the Ramayana into English, and during the nineteenth century many other Hindu and Buddhist texts were translated by European scholars. The philosopher Schopenhauer (1788-1860) was influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. By the late nineteenth century the work of scholars such as Max Müller (1823-1900), who edited the Sacred Books of the East, and Rudolf Otto (1869-1937), as well as the teachings of the Theosophical Society, were creating small circles of friends who were fascinated by the Wisdom of the East. In addition, a number of Europeans who worked for a time in the colonies had contact with other religions and, in most ports, their small immigrant communities.

Some Anglicans, such as Bishop Brooke Westcott or the missionary C. F. Andrews, acknowledged the presence of the “True Light” in other world religions. Several Europeans were present at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, and as early as 1869, the opening of the Suez Canal was marked by “religious services of a somewhat mixed character, Mussulmen and Roman Catholics each taking part.”

In the opening years of the twentieth century, four congresses of what is now known as the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF) were held in Europe: London (1901), Geneva (1905), Berlin (1910) and Paris (1913). The Church Peace Union, which was founded by Andrew Carnegie, with some Jewish participation, arranged a peace conference in Constance, Germany, in 1914, which came to an abrupt halt when war was declared – although the Fellowship of Reconciliation in part owes its origins to that gathering.

All this was 80 or more years before ‘dialogue’ and ‘interfaith’ entered the dictionary. ‘Interfaith’ is not in my 1991 Concise Oxford Dictionary, and there is still debate whether you need two words – ‘inter faith’; a hyphen, as in ‘inter-faith’; or one word – ‘interfaith.’

First Seeds

The period between the two World Wars saw some growth in the academic study of religions. It was largely thanks to Sir Francis Younghusband – an explorer and mystic – that any attempt was made to educate a wider public. A “Religions of Empire” conference was held in 1924, and subsequently a Society for the Study of Religions was formed. Younghusband’s most lasting achievement was founding the World Congress of Faiths (WCF) in London in 1936, in which leading scholars from around the world participated. Few religious leaders showed any interest. On the Continent, Rudolf Otto, known for his book The Idea of the Holy, was active in the ‘Inter-Religious League,’ and Norman Bentwich proposed a ‘League of Religions.’ In 1939, WCF’s annual conference was held in Paris, and subsequently L’Union des Croyants was formed, in which Teilhard de Chardin participated.

In Britain, during World War II, leaders of the churches and the Chief Rabbi came together to found the Council of Christians and Jews (CCJ). They also joined colleagues across the Atlantic in supporting the “Three Faith Declaration,” which helped prepare for the U.N. Charter. Suggestions that the U.N. needed a Religious Advisory Council, however, came to nothing.

In the years after the Second World War, WCF struggled to survive and CCJ gained some support, whilst for years continental Europeans were struggling to rebuild national and church life. With imperialism on the wane, interest in other religions was largely confined to supporters of the missionary societies and a few academics. Under the influence of Karl Barth and the missionary theologian Hendrik Kraemer, the gulf between the Gospel and religions was emphasised. In any case, the struggle with atheistic Communism and Fascism, as well as with a new intellectual climate influenced by Darwin, Freud, and Biblical criticism, were higher on the churches’ agenda.

Slowly the arrival of immigrants created some interest in their religions. Rudolph Boeke established a center for religious contacts, Interreligio, in the Netherlands in 1972. In Britain religious education in schools gradually included some teaching about other religions besides Christianity. Yet, as late as 1980, Clifford Longley, then religious affairs correspondent of The Times, observed that the churches showed hardly any interest in other religions – and the same was true for much of Western Europe. Communist countries discouraged any religion.

A Movement Emerges

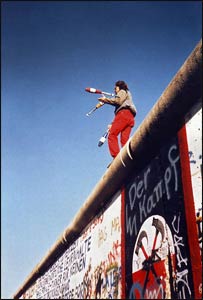

A juggler celebrates the destruction of the Berlin Wall, November 1989 – Photo: Wikipedia

By the eighties the situation was changing. Both the Geneva-based World Council of Churches and the Vatican were encouraging Christians to dialogue with members of other faiths. In 1986, Pope John Paul II invited religious leaders to join him at Assisi for the first World Day of Prayer for Peace. The Second Assembly of the World Conference on Religion and Peace was held in Belgium and subsequently a European Committee was established. IARF – then based in Frankfurt – was becoming a genuinely interreligious organisation. In Britain, the Inter Faith Network was established in 1987. There was increasing Christian-Jewish dialogue and some efforts to include Muslims. There were also a number of local initiatives.

The nineties were a time of hope. The Berlin Wall came down in 1989 creating a new situation for religious communities in Eastern Europe and opening up communication with the rest of Europe. An Interfaith Global Forum on the Environment was held in Moscowin 1990. Numerous events were held during the “Year of Interreligious Understanding and Co-operation” in 1993, marking the centenary of the 1893 World Parliament of Religions.’ The Three Faiths Forum, which quickly spread its influence beyond Britain, was set up in 1997. Yet the optimism with which the new Millennium was greeted was soon shattered by 9/11, by other acts of terrorism, and the military response to them.

Violence and Dialogue both Growing

The early years of the twenty-first century have seen an alarming increase in religious extremism and communal violence. At the same time, we witness a rapid growth of interfaith and intercultural dialogue at local, national, and international levels, as well as the academic study of religions, in all of which Muslims have been playing an increasingly important part. In 2012 the King Abdullah International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID) was opened in Vienna. Europeans have also shared in the growth of the United Religions Initiative (URI), and the third Parliament of the World’s Religions was held in Barcelona in 2004.

It is also now common to invite guests of other faiths to events organised by a particular faith community. Yet, perhaps even more important than the growth of interfaith dialogue is the increase in multi-disciplinary dialogue in which people of different faiths and disciplines engage together in addressing major issues such as conflict resolution, economic injustice, effective action to prevent genocide, and protecting human rights and the environment.

The story briefly summarised here is told with much more detail in my books Widening Vision www. Lulu.com and Kindle, (ISBN 978-1-291-36232-9); Pilgrimage of Hope, London, SCM Press, 1992 (ISBN 0-334-02500-1); and Religion in Europe, eds. Sean Gill, Gaviv D’Costa and Ursula King, Pharos, 1994 (ISBN 90-390-0508-7).