By Phillip Goldberg

SHARING WHAT AMERICA IS LEARNING

I first became intoxicated by India as a college student in the 1960s, through the movies of Satyajit Ray, the music of Ravi Shankar and, most of all, the revelations of the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads. My first exposure to these sacred texts came second-hand, through the work of interpreters like Alan Watts and Aldous Huxley and the fiction of Herman Hesse, Somerset Maugham, and J.D. Salinger. The Beatles put me over the top when they took up Transcendental Meditation and made their landmark pilgrimage to Rishikesh. The total effect of those cross-cultural hinges was to turn this existentialist/atheist/social activist into a dedicated spiritual seeker. I’ve been immersed in yogic practices and Hindu texts ever since.

The Beatles with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh, India – Photo: Wikipedia, Paul Saltzman

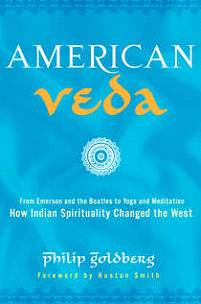

Over the years, I saw the teachings of India’s sages transform the lives of millions of people who took up meditation, stretched and bent in yoga studios, visited ashrams and sat with gurus. I saw Hindu-based ideas and practices filter into mainstream culture through health practitioners, psychotherapists, research scientists, scholars, and artists. Eventually, I wrote a book, American Veda, chronicling the East-West transmission from the days of Emerson and Thoreau to the present. The book was well-received, and I vowed that when it was published in India I would go there to tell the Indian people how much their spiritual heritage influenced me and my fellow Americans.

That dream came true in 2013 when the India Foundation, a cultural nonprofit in Delhi, organized a speaking tour to launch the Indian publication. In 30 days, I visited 18 cities in 12 states and gave 28 presentations: public lectures, private talks to select audiences and presentations at high schools, universities, and yoga academies. I was on 11 domestic flights, plus trains and countless automobiles.

High tech is highly visible in India today. – Photo: Infosys

I was in big cities and small, and in ancient towns held sacred by Hindus (Rishikesh, Haridwar, Varanasi). When I describe my schedule, people say, "It must have been exhausting." I tell them, yes, it was physically demanding, but it was always exhilarating, mentally and emotionally, and on the whole extremely gratifying. I would do it again tomorrow, happily and enthusiastically, only with a bit more downtime.

It was exciting to see India in the midst of its explosive modernization. Since my previous visit, six years earlier, changes were evident: infrastructure upgrades like highways, Delhi’s new

Metro system and sparkling airports; gleaming office buildings that have taken root like banyan trees; energetic young people carving out a new future for their country.

The makeover is not complete, of course. Thankfully, much of India’s unique and timeless character remains: the vivid colors, the captivating scents, the welcoming faces, and of course, the palpable sense of holiness, in temples huge and tiny, in wayside shrines, in chants both whispered and blared through tinny speakers, in the eyes of gurus, monks and ordinary people fingering japa beads and doing pujas in their shops.

The lotus, India’s national flower, is held sacred in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. – Photo: Wikipedia, Peripitus

Because I was hosted by gracious, generous, and impeccably courteous people, I got to see places that most tourists do not even know exist. I visited homes and ate what Indian families eat. Most precious of all, I had meaningful conversations with people from all walks of life: politicians, professors, entrepreneurs, corporate executives, retired generals, students, engineers, swamis, gurus, yoga masters, taxi drivers, hotel clerks, mothers and fathers. As a result, I learned more about contemporary India than I could possibly discern as an ordinary traveler. To sum up a multiplicity of impressions, India as a whole seems to be walking on a razor’s edge, an image

first employed in the Upanishads – with modernity and material progress beckoning on one side and its precious spiritual heritage open-armed on the other. The country’s welfare might well hinge on its collective sense of balance.

Hinduism and American Culture

This spiritual/material, ancient/modern tension was explicit in my conversations and in the responses to my lectures. My talks summarized the message of American Veda: Over the course of 200 years, Americans have been imbibing the essence of Hinduism – primarily the philosophical insights of Vedanta and the methods and principles of Yoga – through a variety of streams and tributaries. That transmission, I said, is largely responsible for a huge shift in the way Americans understand religion and engage their spirituality, and it could be one of the most important developments of the modern era.

Most in attendance were proud to hear that their heritage has influenced Americans for the better. Some, especially the young, were surprised by my message, because they themselves considered the spiritual and philosophical aspects of the Vedic tradition irrelevant to modern life, even an impediment to the material progress of their families and their nation. That the most prosperous and innovative nation on the planet had found value in what they had rejected – “Grandma’s superstitions” as one student disdainfully put it – was more than intriguing to them.

It was precisely because Indian youth look to America as a model of progress worthy of emulating that my hosts urged me to emphasize that their spiritual heritage can complement modernization, not impede it. At first, I was not sure how to address the issue. I did not want to sound like I was preaching to them. Nor did I want to come across as an arrogant American telling them how to think. As an outsider I had to be humble, but as the author of a well-researched book I had information to impart.

Ultimately, I settled on this strategy. Think of America as the laboratory of the world, I suggested. Americans are good at inventing new things and experimenting with imported ideas and products. When something proves to be useful, we adapt it to our specific needs and integrate it into our way or life. Sometimes, I added, we modify or redesign useful things and sell them to the rest of the world. America experimented with Vedanta, yoga, and other components of the Hindu dharma and found them to be compatible with – and helpful antidotes to – modern life. In short, the ageless teachings of India’s rishis are not antiques to be stored in museums and libraries. That, I said, is a message from America worth paying attention to, as opposed to the marketing messages that promote junk food, gadgets and fashions.

In the Q&A sessions, I was asked about everything from American foreign policy to “Slumdog Millionaire.” The most pertinent queries from an interfaith perspective were, “Do Americans care about the spiritual components of yoga, or only the physical benefits?” and “Has there been a backlash from fundamentalist Christians?” Those are complex questions, and the short answers are: “Some do, some don’t” and “Yes, but less than you think.”

To my surprise, the most frequent line of inquiry – often more of a discourse than a question – had to with the aggressive missionary campaigns funded by American Evangelicals. The anger, frustration, and resentment was palpable, and the descriptions of devious, coercive, and unscrupulous tactics that missionaries sometimes use to “harvest souls” were painful to hear. (I described some of those stories in this article.) I could not adequately respond to their concerns, but I did inform them that most American Christians would be appalled by such tales.

Hindu-Christian Tensions

It is in that context that recent news items from India about Hindus reconverting Christians and vandalism at churches should be understood. It is in large part a backlash against centuries of aggressive conversion, which is viewed by Hindus as religious imperialism. They can’t imagine why anyone would want to convert another person, because historically and culturally India has always been innately pluralistic. The entire notion of conversion as we know it is alien to the Dharmic traditions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism).

In his appearance at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, Swami Vivekananda deplored the missionaries who help the hungry “only on condition that the Hindus become Christians, abandoning the faith of their fathers and forefathers.” He added, “Do I wish that the Christian would become Hindu? God forbid. Do I wish that the Hindu or Buddhist would become Christian? God forbid.” For the sake of India’s future as a harmoniously diverse nation, one hopes that all its inhabitants, and all of its visitors, will honor the words of the venerated swami.