The Fifth Vow

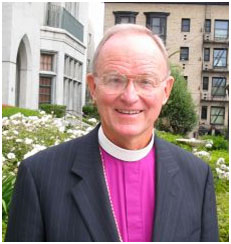

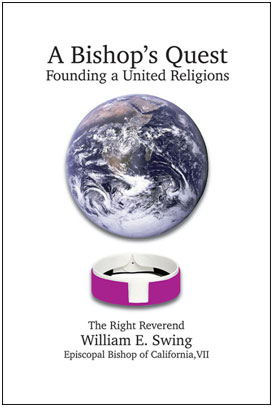

On the afternoon he received the life-changing call, William E. Swing had been the Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of California for 14 years. At 57, his life was richly framed by four vows, as a husband, a deacon, a priest, and a bishop. He left a vibrant pastoral ministry in Washington DC in moving to San Francisco as a bishop. From Grace Cathedral atop Nob Hill, he quickly became known as a pioneer in responding to HIV/AIDS and homelessness, and a major stakeholder in addressing the needs of the elderly, immigrant ministries, and drug and alcohol rehab programs. Some touted him as a future presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church. His new book, A Bishop’s Quest: Founding a United Religions (2015), tells the historic story of what he did instead.

The Fifth Vow

Bishop Swing at Grace Cathedral last month – Photo: Grace Cathedral

Bishop Swing at Grace Cathedral last month – Photo: Grace Cathedral

The fateful phone call came on “a dreary day in February 1993” from Gillian Sorenson at the United Nations. “Would you host a large celebratory event at Grace Cathedral?” she asked. In 1995 the U.N. would be 50 years old and wanted to return to the City by the Bay to commemorate the 1945 San Francisco signing of the U.N. Charter. Swing said he’d “be honored.”

She said that 185 ambassadors from around the world would be coming and then asked,

“Would you bring representatives of all of the religions of the world?” I was so stunned by the question that I deadpanned, “I’m not doing anything much this afternoon and I’ll make a few phone calls.” My silly response was merely an effort to buy time as the profundity of her request began to work its way into my brain.” (p. 13)

Thinking about nations and religions that night, Swing had trouble sleeping. The nations “had forged a common vocation for the good of the world.”

For fifty years they had met. On the other hand, during the same fifty years, the religions had never come together for one day to exercise a common vocation for the good of the world. The world’s religions have no heart or no courage to serve the world together. In my mind it seemed that what was needed was a United Religions to provide religions with a place to gather, to hold each other accountable, and from which to take joint actions for the world’s sake. (p. 14)

That night Bishop Swing decided to accept the challenge of gathering the world’s religions for the U.N. celebration. From this seed came his fifth vow – to find “a way for people of all faiths to keep their faith and at the same time realize a common vocation for the sake of the world.”

Twenty-two years later there are 650+ United Religions Initiative Cooperation Circles in 85 countries, each one of them endorsing Bill Swing’s fifth vow. Achieving this entailed a tumultuous journey with crazy risks, terrible disappointments, unexpected achievements, and a new kind of collaborative, interreligious global network. Each Circle is independent, self-funding, and totally committed to a vision captured in URI’s purpose statement: … to promote enduring, daily, interfaith cooperation, to end religiously motivated violence, and to create cultures of peace, justice, and healing for the Earth and all living beings.

The Story

A Bishop’s Quest – Founding a United Religions is much more than a memoire, though it qualifies. Essentially, though, it is a passionate confession and appeal, a series of compelling stories that read like a picaresque novel, including events some would call miracles. Several factors make it particularly compelling. The bishop is brutally honest, starting with himself. He is open, transparent and vulnerable about everything that didn’t work in his quest. Laugh-out-loud humor and gifted story-telling make it go down easily.

Three years into the quest, for instance, he and Mary, his staunch partner through thick and thin, plan a mad-cap, “bare-bones schedule,” three-month sabbatical trip around the world to enlist major religious leaders in the vision. First stop, Southwest India, where they expected to be picked up at the Cochin airport and taken to a massive Protestant gathering on a riverbank.

… But no one was there in that blisteringly hot airport. We sat for hours on our luggage, and since no one spoke English, we sat quietly. At last a little man in a yellow-orange suit emblazoned with a large, cheerful badge came and asked: “Bishop?” I leapt toward him in relief. When I turned to introduce my wife to him, the look on his face indicated that I was the wrong kind of bishop. It turned out that the Roman Catholics were having a convention in the area, and his job was to pick up dignitaries at the airport. So we got back to waiting. (p. 57)

The problems didn’t end at the airport. On the banks of the Pamba River, preaching to thousands about the Good Samaritan, he mentioned his quest to create a United Religions. “A large, ferocious verbal confrontation ensued. People started clambering out of the jungle with Bibles in hand stating that salvation came only through Jesus…” (p. 59) Weeks later he spoke at Oxford University, a familiar, comfortable environment for an Episcopal bishop: “The audience by and large disapproved of my whole speech.” (p. 95)

Visiting the Vatican was even tougher. San Francisco’s Archbishop William Levada had helped secure an appointment with Cardinal Francis Arinze, head of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. At a Saturday meeting, Arinze greeted Bill and Mary with warm hospitality. But on Monday, having read Swing’s Oxford speech, Arinze “stormed into the room … and announced that the Roman Catholic Church would never have anything to do with the United Religions … Why? First of all, he said that Jesus Christ sent them out to evangelize the world, not to unite the religions. Then he went on to say that it would not be fair for a recent and small religion or a weird offshoot religion to be at the table as an equal partner with an historic worldwide religion.” (p.110)

What kept the Bishop going in face of the roadblocks? He learned from each criticism, treating them as lessons, not affronts. Equally important, he was doggedly persistent, and the doors started to open. In India, the Dalai Lama, Karan Singh, Syed Ahmad Singh, and Mother Teresa were among the religious luminaries who were positive and supportive. In Egypt the Grand Mufti, Mohammed Sayed Tantawi, and His Holiness, Shenouda II, Pope of the Coptic Church, both gave their blessing, as did the Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch, His Holiness, Bartholomew, in Istanbul. Theologian Hans Küng, perhaps the most influential Christian champion of interreligious relations, spent hours advising the Bishop. And Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey “could not have been more engaging and supportive.”

Creating a New Kind of Organization

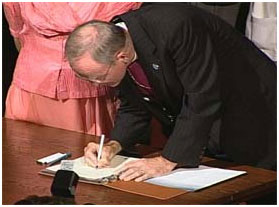

Bishop Swing, the first of many thousands, signs the URI Charter in 2000 in Pittsburg – Photo: TIO

Bishop Swing, the first of many thousands, signs the URI Charter in 2000 in Pittsburg – Photo: TIO

In 2000, four years after this initial journey, the URI Charter was signed in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A Bishop’s Quest is chock-a-block with stories about the two decades it took to build the largest grassroots interfaith organization in the world. Dee Hock’s chaordic insights into organizational development and David Cooperrider’s pioneering discipline of appreciative inquiry each played major roles. Taking risks continued to be the Bishop’s hallmark. At one point the Swings took out a $1 million personal mortgage on their home and assets to keep URI alive; one of the most gratifying tales is how they got paid back. More than once in those days the Bishop was known to say that creating URI was like building an airplane while flying it. Along with all the difficulties, though, something new and vital was created and keeps growing, new Circles joining every month.

Still, a wistful undertone pervades the book, Bill Swing’s disappointment that the leaders of the world’s religions have not seen the wisdom of actually incorporating into a collaborative global force to better the planet, as have the nations. United Religions remains the United Religions Initiative. But he’s learned to be a patient man.

In community organizing, a familiar trope suggests that ‘where the people lead, the leaders will follow.’ If the bishops and hierarchs of religion can’t find the wherewithal to care as much about humanity and the planet as for their particular traditions, people of faith and practice at the grassroots will lead the way. It has already begun. And Bishop William E. Swing is a major contributor in making this spiritual revolution possible.