TIO Public Square

Dialoguing at the Square

by Robert P. Sellers

Debating opposing ideas in contemporary America is a growing industry. It has become much more than a school extracurricular activity or community service club program.

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN DEBATES

Much debate today, not surprisingly, is political.

Charlie Kirk was an extremely popular “political activist, entrepreneur and media personality” among conservative young Americans prior to his tragic assassination in September 2025, and perhaps even more so afterwards. Kirk founded the student organization Turning Point USA in 2012 and was its executive director until his untimely death. TPUSA has strong connections with the MAGA movement and collects thousands of donations from conservative donors. In 2020 alone, Turning Point had more than $39 million in revenue. Kirk’s daily three-hour radio talk show, aimed at Generation Z, was “downloaded between 500,000 and 750,000 times each day in 2024” [Ibid.]. He was best known, however, for his visits to college campuses, where he would publicly debate students to persuade them to embrace conservative values, policies and candidates. That’s what he was doing at Utah Valley University when he was murdered.

Dean Withers is a liberal political commentator, content creator and live streamer on Tik Tok, X, Facebook and You Tube. The 21-year-old loves to surround himself with a circle of conservative opponents, present them with a series of political claims – for example, “Democrats are more patriotic than Republicans” – and invite them, one at a time, to join him at a table in the center of the circle for a brief, timed debate. Withers demonstrates a ready grasp of facts supporting his claims, which often makes it difficult for those opposing his views to counter his arguments. The New York Times suggests that he may be one of the Democrats’ “Tik Tok Bro Whisperers” who, like Kirk, desires to win the support of young, male followers. His most famous debate with 20 MAGA followers – recorded on Jubilee, a Los Angeles-based media company which specializes in facilitating debates about social issues – has had more than 10 million views. Withers also has millions of followers across his many platforms, with some 4.5 million on Tik Tok alone.

Besides politics, debates about religion and God are prevalent today as well, resurrecting a stream of sometimes combative confrontations that has ebbed and flowed throughout the centuries, but which has come to life again in contemporary society.

Alex O’Connor is a 26-year-old English public speaker, writer, social media figure and graduate of Oxford University who, as a self-identified atheist, loves to debate theists about philosophy and theology. On his video channel called the “CosmicSkeptic,” he has interviewed noted atheist authors Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. In a format similar to the one used by Dean Withers, O’Connor has faced 25 encircling Christians to argue the existence of God. One of his claims in his own Jubilee debate was “suffering makes God’s existence unlikely” – a reference to the classic theodicy question. A more famous British discussion of theodicy featured Stephen Fry – actor, comedian, humanist and atheist – and John Lennox – mathematician, bioethicist, lay theologian and retired Oxford professor who has earned doctorates in three academic fields. Less scholarly is the work of Allie Beth Stuckey, a wife and mother who hosts a podcast called “Relatable” where she analyzes news, culture and theology from a conservative Christian perspective. Again, using the same format at Withers and O’Connor, Stuckey sits surrounded by progressive Christians who debate her various claims, such as “The Bible says that marriage is only between one man and one woman.”

Religious debates between people of different faiths are also common. These can be academic discussions on university campuses or in public fora, exploring two or more approaches to common dilemmas, such as the wealth gap or climate change. Alternately, such disputes might be apologetic in nature, defending one’s personal religion and refuting the other’s. Or, the disagreements might be personal exchanges, occurring in less formal settings among friends or acquaintances.

One incident of formal interreligious discussion took place in 2012 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City – a panel moderated by Professor John Esposito of Georgetown University on the topic “People of the Book: Muslims, Jews and Christians.” Three distinguished teachers – a Christian from Oxford University, a Jew from the University of Southern California and a Muslim from Smith College – engaged the topic before an appreciative audience.

In all these various debates in the public square, dialogue was being attempted. The same can be said for any conversations, however pleasant or contentious, that occur at the locus of public opinion – across the conference stage, social media platform, dinner table or backyard fence.

WHAT IS DIALOGUE?

Since my career has been spent in both practical and academic arenas of religion rather than politics, my understanding of the meaning and best practices of dialogue is drawn from my more than five decades of Christian and interreligious relationships and interactions. I have been an ordained minister for 50+ years – engaging fellow Christians primarily in North America and Asia – but I have also been involved in the interreligious movement for at least a quarter century. I confess it has been my work alongside persons of other religious traditions which has most stirred my passions. I share these comments about dialogue because I have discovered them to lead to authentic friendships and cooperative partnerships.

In 1971, the World Council of Churches, based in Geneva, Switzerland, formed a sub-unit on Dialogue with People of Living Faiths and Ideologies, chaired by Indian theologian Stanley Samartha, and later by Sri Lankan minister Wesley Ariarajah. The sub-unit they led has contributed greatly to the beneficial practice of dialogue, both religious and otherwise [See Martin Forward, Inter-religious Dialogue: A Short Introduction (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2001), 11]. For the global ecumenical Church to recognize that we live in a multireligious world where it matters how people of various faiths relate to one another was a highly significant moment in modern Christian history.

Professor Martin Forward notes that “dialogue” is often contrasted with “monologue,” suggesting the best dialogicians listen to their conversation partners with respect and genuine interest, rather than simply or solely talking or airing their own viewpoints. He explains that the Greek prefix in the word is “dia” and not “di.” The word is not “di-logue.” “Di” is the Greek prefix meaning “two,” which is how one typically understands this process as the back and forth speaking of two or more persons about their individual perspectives. But “dia” is a preposition which means “through.” Thus, says Forward, “dia-logue” signifies worldviews being argued through to significant conclusions. It involves a much more consequential encounter., … [where] the conclusions [the participants endorse may] be modified or even changed in the context of listening to others” [Ibid., 12].

WHY IS DIALOGUE IMPORTANT?

James Heisig, the director of the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture in Japan, and an expert in the relations between two great missionary religions – Buddhism and Christianity, declares that the time for religious conquests of other faith traditions is past. According to his view, the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road beginning in the first and second centuries, or the global expansion of the Christian world in the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, cannot be replicated today. He writes, in Dialogues at One Inch above the Ground:

Hopes of winning the whole world over to a single religious organization still linger from the past, but they ring shallow and out of key with the religious consciousness that has taken shape in the twentieth century and [has propelled] us into the next millennium. The interreligious dialogue that has come to flower over the past twenty years among world religions … has been instrumental in re-directing religious faith away from the dream of redrawing the religious geography of the world, and towards the dream of cultivating insights and virtues suited to coexistence in a religiously plural world [James W. Heisig, Dialogues at One Inch above the Ground (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2003), 107].

It was Hans Küng, Swiss Catholic priest and professor of ecumenical theology at Tübingan University in Germany, who in 1996 published Christianity: Essence, History and Future – one of the more than 70 books he wrote or edited during his career. That book contains the famous assertion of Küng’s which he frequently referenced until the end of his life: “No peace among the nations without peace among the religions. No peace among the religions without dialogue between the religions” [Hans Küng, Christianity: Essence, History and Future (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1996)].

Dialogue can help people of different religions and ideologies begin to treat one another as neighbors and friends. Whether they are atheists, Baha’is, Buddhists, Christians, Confucians, Daoists, Hindus, Indigenous ritualists, Jains, Jews, Muslims, New Thought adherents, Pagans, Secular Humanists, Shinto followers, Sikhs, Spiritualists, Unitarians or Zoroastrians, followers of these diverse paths can learn to live together peacefully.

It is not a matter of developing toleration for others, however, where one simply allows another to occupy nearby space. Rather, peacemaking demands personal humility, careful preparation, patient deliberation and mutual respect.

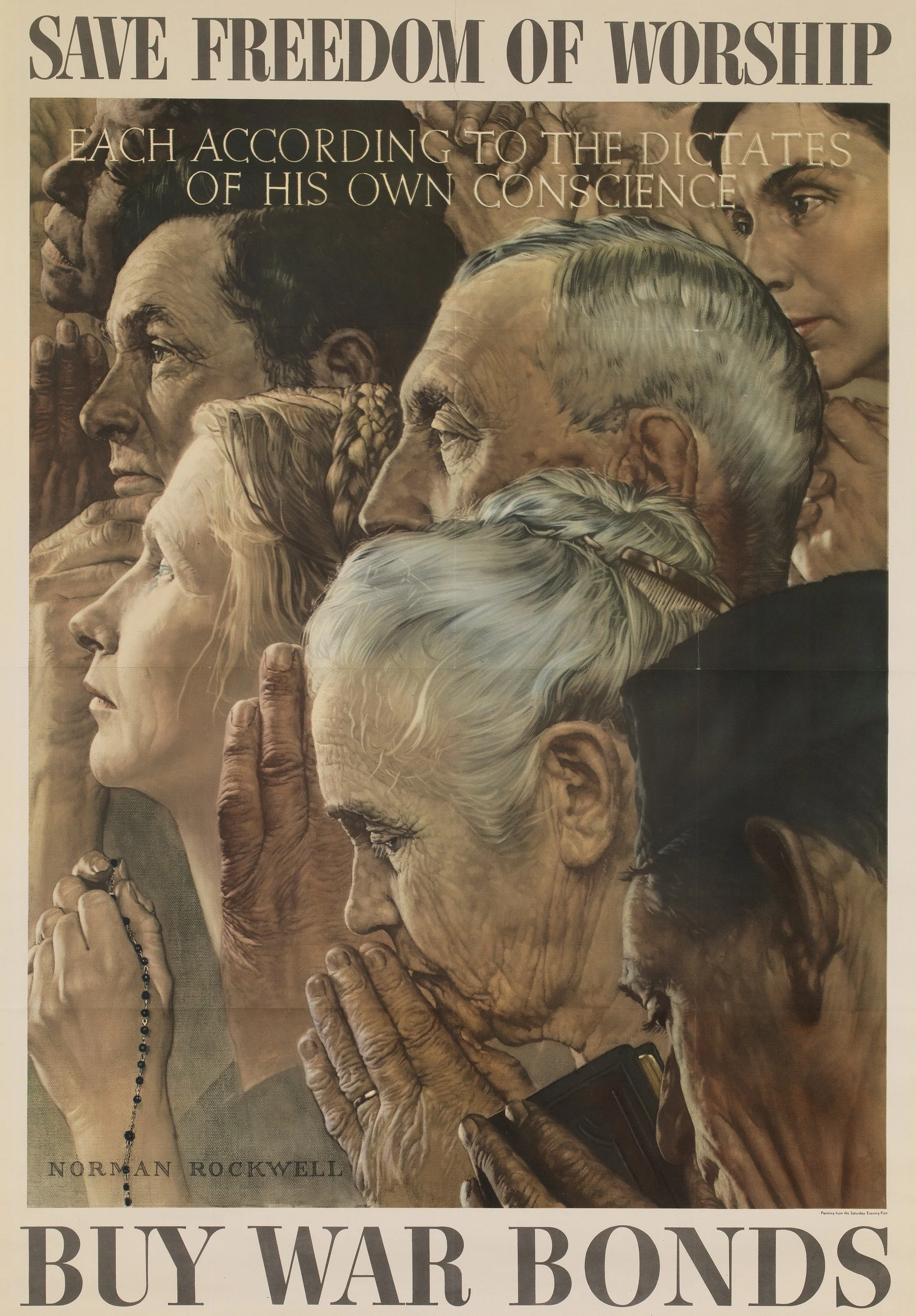

Norman Rockwell was an iconic American painter and illustrator who celebrated American life in his art. Following President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address, Rockwell completed a series of four oil paintings in 1943 called the Four Freedoms. The one illustrating freedom of worship depicts the faces of eight individuals – men and women, racially different, perhaps representing diverse religions, each engaged in prayer – all facing in the same direction. In another painting, reflecting Rockwell’s concept of freedom of speech, a young man is standing to speak in what might be a small New England town hall meeting. On either side of this speaker, who wears an old jacket and work shirt, are seated two older men in coats and ties. Their facial expressions show that they are carefully listening to the younger, perhaps less formally-educated, neighbor. The paintings depict important principles of community best practices: joining, across differences, in the common task of doing sacred and unifying work, seriously engaging in both speaking and listening [Gustav Niebuhr, Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America (New York: Viking, 2008), 53-54].

PRINCIPLES OF DIALOGUE

In 1977, a World Council of Churches conference in Chiang Mai, Thailand, developed a document called “Dialogue in Community.” This document became the basis for the first set of guidelines, or principles, produced in 1979 by the World Council, titled Guidelines on Dialogue with People of Living Faiths and Ideologies. Translated into many languages, the statement contained four principles of dialogue:

1. “Dialogue should proceed in terms of people of other faiths, rather than of theoretical impersonal systems.” Engage your dialogue partner as a person, rather than addressing, merely intellectually, their religion, political agenda or philosophical position; keep the conversation on a person-to-person basis.

2. “Dialogue can be welcomed as a way of obedience to the commandment of the Decalogue: ‘You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.’” Tell the truth about your dialogue partner and the beliefs he or she espouses.

3. “Dialogue … is a fundamental part of Christian service within community.” Treat your dialogue partner with respect, as a neighbor to be known instead of an enemy to be defeated.

4. “The relationship of dialogue gives opportunity for authentic witness.” Confess your own faith without manipulating your fellow pilgrim or denigrating his or her tradition. [Kenneth Cracknell, In Good and Generous Faith: Christian Responses to Religious Pluralism (Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press, 2005), 100].

To these official principles for dialogue attributed to the World Council of Churches, I add the following suggestions drawn from my own experience over several decades of interreligious friendships and work:

5. Enter into dialogue when both you and your partner have decided you wish to converse about a particular topic. Honor your dialogue partner’s right to choose when to debate an idea or practice, instead of forcing the conversation upon him or her because you have something you want to say.

6. Listen respectfully to what your dialogue partner is saying. Remember that genuine conversation with your dialogue partner requires both honest speaking and careful listening, knowing that the times when your partner is speaking are not simply opportunities for you to be thinking about your next line of argument.

7. Go into the dialogue with open-mindedness, being willing to change your own mind if you are convinced of the truth of your partner’s position. Recognize that entering a dialogue with your mind already made up, convinced your partner can teach you nothing, dooms the dialogue to failure before it even begins.

8. Earn the right to share your views in dialogue because of the neighborly ways you have acted toward your partner before you ever sit down to converse. Recall the familiar maxim that people don’t care what you know until they know that you care.

CONCLUSION

In contemporary America – where political opponents have become enemies to hate, and persons of faith traditions different from our own may be seen as dangerous strangers to fear, it is important that in the public square we learn how to dialogue with others. Screaming, belittling, name-calling, lying, exaggerating, berating, interrupting, humiliating, or shutting down are not ways that facilitate neighborliness or build peace. Comparing the best of our own tribe with the worst of our partner’s community is dishonest and unfair.

Recognizing the nature and importance of dialogue is important in our current society, which is torn by partisan ideas about politics and religion. Embracing and practicing the principles of good dialogue will not only make us more proficient debaters, but also can help us become less contentious persons, more amiable conversationalists and – most important – better human beings. Dialoguing in the public square is almost a required activity in our society. When we choose to debate, I hope we will remember that dialogue is a freedom and privilege which democratic society both allows and promotes.