TIO Public Square

Huston Smith on Public Virtues and Vices

by Robert P. Sellers

Huston Cummings Smith (1919-2016) was an American professor and author, in my opinion the greatest world religionist of the 20th century.

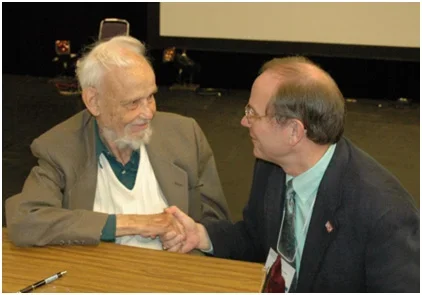

Robert P. Sellers meets Huston Smith at Montreal conference in 2006.

His book, The World’s Religions (originally titled The Religions of Man), was reprinted 65 times and had sold more than 3 million copies by 2017. It was my incredible honor to meet Smith at an international conference in Montreal in 2006, organized around the theme, “The World’s Religions after 9/11.” I wrote about the impact for me of meeting this remarkable leader in a 2017 article in The Interfaith Observer titled “Huston Smith and the Parliament of the World’s Religions: Heroic Interfaithing.”

Having grown up in China, the son of Methodist missionaries, Smith began to admire the world’s great religious traditions, although he remained a faithful Methodist Christian all his life. During his academic career, he held teaching posts at Washington University in St. Louis, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Syracuse University and, in retirement, the University of California at Berkeley. While his primary field of research, writing and teaching was the world’s belief systems, Smith was also a highly respected philosopher.

HUSTON SMITH AND BILL MOYERS

Bill Moyers was the eleventh White House Press Secretary from 1965-1967, during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. For more than five decades, he was a broadcast journalist who interviewed hundreds of prominent icons of politics, business, religions, philosophy, science, and culture. He received a Peabody Award, the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, and an honorary doctorate from the American Film Institute. Perhaps his most watched interview, however, was his 1996 five-part PBS series with Huston Smith called “The Wisdom of Faith.” The episodes covered Hinduism and Buddhism, Confucianism, Christianity and Judaism, Islam, and Smith’s personal philosophy of religions. The central theme which Smith stressed with Moyers was that universal truths can be found across the major faith traditions.

THE HUSTON SMITH READER

Jeffery Paine, author and editor, worked with the esteemed philosopher of religions to produce The Huston Smith Reader (2012). In his introduction, Paine tells his readers about Smith as a teacher. He writes:

The most important thing Huston discovered was that there are radically different ways of being. Different people have contrary emotional responses to the same social stimulus; they give the same phenomenon opposite interpretations and then mistake that interpretation for the objective world. Venturing beyond Judeo-Christianity, Huston was amazed: all people believe alike even less than they all physically look alike. Dissimilar predispositions had proliferated into divers paths to salvation. In Hinduism, for instance, there are four basic human temperaments, hence there are four kinds of yogis – [‘methods of training designed to lead to integration or union of the person’]. There are Karma yogis (e.g., Gandhi) who attain liberation through action, and there are bhakti yogis (e.g., Saint Francis or Mother Teresa) who have great feeling and love their way to salvation. Raja yogis (e.g., the Buddha) meditate their way there, while jnana yogis reach the ultimate goal through intellect or vision. Thus Huston identified himself as a jnana yogi, somebody who could use his intelligence, his teaching and writing, to help re-sacramentalize the world.

Huston Smith and world religion symbols.

The book, as Smith organized and Paine edited it, is what the editor calls “a grand tour.” It is comprised of five “books” or sections of Smith’s essays, each leading logically into the next. Smith’s 23 essays and conclusion had all been published before, enabling Smith and Paine to collect the religionist’s most important thoughts for a new generation of readers.

“THE SACRED DIMENSIONS OF EVERYDAY LIFE”

Book 2, or section 2, designated “The Sacred Dimensions of Everyday Life,” includes an essay with this same title – one published in 1975, soon after Smith had concluded his 15 years as professor of philosophy at MIT. The essay is comprised of an interview between him and professor of educational philosophy, Jeffrey Kane.

Midway through the interview, Kane asks Smith: “Would you say that there are certain universals that one would find through many of the world’s religions?” This is precisely the point at which Smith’s observations become important for those of us who gather at the Public Square. Smith, the jnana yogi, responds to Kane’s query in a way that potentially could help to “resacramentalize the world.” In part, he answers: “Yes. Two levels need to be distinguished here. The one which is the more explicit is what we should do, but beyond that is the question of the kind of person we should try to become.”

APPLYING THE WISDOM OF HUSTON SMITH

As we gather at the Square, perhaps with persons radically different from ourselves, we need to remember that being is more important than doing. Who I am and who you are is more significant to our living together than what I do and what you do. How strange, indeed, that the first and perhaps primary question we ask a stranger is “What do you do for a living?” A better question would always be “Who are you trying to be or become in this life?”

Continuing, Smith explained:

Now, on the first level, what we should do, there are four problem areas in human life that have to be dealt with. These are violence, wealth, the spoken word, and sex. In lower forms of life these problem areas are monitored quite adequately by instinct. [A human being], though, is an animal without instincts, so these problem areas can get out of hand. Moral precepts are devised to secure appropriate, life-sustaining behavior in the four areas, and they are remarkably uniform across cultures: don’t murder, don’t steal, don’t lie, don’t commit adultery. These are the basic guidelines concerning human behavior.

Each of these four problem areas can impinge upon our meetings with the Other at the public square. Sometimes, because of disagreement, one’s voice reveals rising anger, so violent words, even actions, can result. Socioeconomic differences between dialogue participants can create distance even before the first words are spoken. Untruths or half-truths about one’s own perspective, or the position advocated by one’s opponent, can hinder communication. Judgments about the gender or sexuality of the person with whom one speaks can destroy the possibility of agreement or compromise. These four basic challenges to productive life together – similarly identified in all the world’s major religions – can often be seen lurking about the Square.

Smith turns to the other level of universal experience:

As for the kind of person we should try to become, the virtues point the way. In the West, these are commonly identified as humility, charity, and veracity. Humility has nothing to do with low self-esteem; it is to recognize oneself as one and fully one but not more than one, just as charity is to look upon your neighbor as fully one (with all the rights and privileges pertaining thereto) just as you are one. Veracity begins with not being deceitful, but it ends in the sublime objectivity that sees things exactly as they are, undistorted by our subjective preferences. These are the virtues in the West. Asia, interestingly, has the same three [virtues] but enters them by the back door, so to speak, by [emphasizing] the three poisons – traits that keep the virtues from flourishing in us. The three [poisons] are greed (the opposite of humility), hatred (the opposite of charity), and delusion (the opposite of veracity). To the extent that we expunge these three poisons, the virtues will flood our lives automatically. The convergence of East and West in these areas is remarkable.

Huston Smith was virtuous. Humility, charity and veracity marked the character of this gentle, wise man. Having read Smith and admired him for decades, I feel certain that his summary of how to become a better person can be trusted. I am convinced that pursuing or nurturing the traits of humility, charity and veracity in our lives will help us to respond appropriately to the troublesome temptations of violence, wealth, the spoken word and sex. If we can resist drinking the poisons of greed, hatred and delusion, then virtue can grow in our lives.

Early in his life, he decided that what he was going to do with his life was to share his fascination with the beauty and wisdom of the world’s great religious systems with as many people as he could. Just as early in his life, he also decided that the beliefs of his missionary parents – which had begun to undergird his own vibrant faith – would shape the person he would become. Smith practiced these virtues which he identified for so many years that his enviable responses to life’s challenges became instinctual.

CONCLUSION

The ways that Smith treated others was exemplary. Although he had traveled the world, was personal friends with Aldous Huxley, Joseph Campbell, the Dalai Lama and other leading philosophical and religious figures, was the author of acclaimed books, had taught at famous universities and had been given multiple awards and commendations, he was approachable, friendly and humble.

He spent a lifetime engaging with others in the Public Square. Regardless of whether they were Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, Native Americans, fellow Christians or persons who walked other religious paths, this professor approached them with genuine interest and respect. It didn’t matter if they were famous scientists, philosophers or academics from multiple other fields of study, or freshmen in his university classes, he listened carefully and responded honestly to all. He was consistently kind and soft-spoken, debating complex issues at one of the high-profile universities where he was a professor, discussing life with seniors in his retirement center or envisioning the future with his own great-grandchildren who sat next to him on the floor.

When I grow up, I want to be just like Huston Smith.